Most professionals in both the property management and bill-collection business agree: serious payment arrears don't happen all that often in HOAs, but when they do, it isn't pretty. Unpaid fees are more than just a hassle; they're a time-drain for managers and their administrative staff, they negatively impact the association's financial profile, and they can cause a lot of bad blood between residents, boards, and management.

Nowhere to Hide

"It's not like the dentist," says Vincent Gaudio of Collex, Inc. in Long Valley, a collections agency that serves HOAs and managers. "If you have a $200 outstanding bill at the dentist and you get a toothache tomorrow, you'll just go to a different dentist and avoid that other bill. With residents, it's different from usual collections because the people are actually living there."

Indeed, there are few places for delinquent condo residents to hide—everyone has to come home eventually. A person might be able to slink around in a huge building, but in a smaller community, it's hard to come or go unnoticed. And, as Gaudio points out, there are many bills people will avoid paying before they'll compromise their living situation—it's usually the last to go unpaid.

"The occurrence of bad debt or bad money in this industry is relatively low, as opposed to the retail industry, for example," says Gaudio. "Again, this is because you're dealing with the place where people live. The medical industry or the auto industry deals with debt a lot more. The occurrence of bad debt in the co-op and condo industry is the lowest in any industry."

Excuses, Excuses

While that's encouraging news, it would be naïve to think everyone pays mortgage payments and maintenance fees perfectly on time, all the time. There's always a reason why the money's not coming—some reasons are just better than others and are delivered in a responsible way. Steve Misetic, a property manager in Chicago, says that the reasons people cite for late or missing maintenance or common charge payments are what you'd expect.

"People get into trouble when they've got a lot of unexpected bills; like medical bills for example," he says. "Car accidents, last-minute airfare for funerals, stuff like that. Of course you have compassion for that sort of thing. For me, though, it all comes down to that person's track record."

Misetic says that if an otherwise responsible resident falls on hard times, it's a lot easier for managers and/or boards to cut that person a break or help them work out a plan that allows them to stay in good financial standing. In the case of residents who sublease their units to rental tenants, it's a matter of making sure the sub-tenants have a healthy financial profile themselves.

"It's all about pre-screening," Misetic says of that subset of residents. "We're really serious about background checks, credit checks, and references. I have little trouble with arrears because we attempt in every way to make sure that the people in the buildings are responsible, trustworthy people—the kind of people who are rarely going to struggle with payments."

A property manager in New Jersey who asked to remain anonymous says that yes, people have reasons for delinquent bills, but quite often property managers and boards never hear them. "Most of the time, you don't get reasons," he says. "If a bill is delinquent, we send statements and just don't hear from [the unit owner] at all."

The manager has some words of advice, both for HOA members struggling to pay this month's common charges, or trying to decide between paying a hospital bill or their condo fees: "Communication helps so much," he says. "If you're going through financial hardship, most property managers and boards will listen and help create a plan to get you through the tough times. With a plan in place, the bills will eventually get paid. The result is dependent on how well the owner can work with the board. Ignoring notices won't get you anywhere."

Taking the Next Step…

If a delinquent owner chooses to go on the lam, so to speak, and ignores attempts made by their management to get to the bottom of the problem, however, he or she will definitely be in for an adventure. The process of collecting arrears from an HOA member is labyrinthine and wound tightly in red tape.

"The board gets a monthly report," says the northern New Jersey property manager. "The report shows who's in arrears. The master deed of the condo will outline what the late charges are—they usually start after a person is 10 days late. Normally, we send a statement to the owner to tell them when their 'grace period' is over. All of an HOA's rules about this are in the title deed. More late fees are assessed, and then there's a letter that tells the person that if they don't resolve the arrears, the bill will go to collections. At that point, the owner usually gets 10 to 30 days to handle the problem. After that, if there's no word at all or they're being nasty, the problem goes to the HOA's attorney who writes what's called a 'demand letter.' If there's no payment within 30 days or so, a lien is filed. Then everyone waits."

Considering that the next step in the process accrues serious cost, it's likely that everyone's waiting for a miracle.

"The manager keeps the attorney informed in case anything should change," says the manager. "And the board president has to sign the lien with a witness present. Since the mortgage company doesn't want a lien on the property, sometimes they'll pay the bill. This doesn't let the owner off the hook, of course. If there's still no payment after a lien is filed, it's pretty much guaranteed you've got a lawsuit on your hands."

Counting the Costs

The costs involved in such a complex, arduous process are another reason why, for most people, it's just easier to find a way—any way—to pay up.

"An eviction is a lose-lose situation," says Misetic. "The HOA loses because they're not getting the rent and/or fees. The non-payer will lose because he or she will have a judgment against them. The court costs are terrible, obviously. It's a costly process."

As is bill collection, though for many HOAs, it's a welcome solution to owners who ignore the pleas from the managers or board to bring themselves up to date financially. The words "bill collection agency" inspire fear in most people—and that's exactly what they want, within reason.

"The collection process is progressive, and there's a reason for that," says Gaudio. "Everyone responds in a different way at a different stage in the collection proceedings. People pay their debts in order of greatest consequence. I don't pay my HOA fees for two, three, four months and nothing happens, I'll ignore it. I'll wait on that bill and pay the guys that are calling me on the phone."

Gaudio says that the "soft consequences" HOAs place on owners don't help an association avoid late payment problems. Bill collectors are there when "soft consequences" need a little toughening up—but, Gaudio stresses, not too tough.

"The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDPCA) is a set of federal guidelines for third party collectors," Gaudio explains. "These guidelines are in place regardless of the type of debt—they address how to handle communication with a debtor. For example, you can only call from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m., and not after that. There's a specific letter that must be initially sent to the debtor that tells them you're intervening, including a balance of their outstanding debt. If [the debtor] disputes that, they have 30 days to do it in writing. The FDPCA [of 1978] forbids abusive language, threats, or warnings about actions you're not actually going to take. Anyone who does collections should be aware of these rules and practice them."

Your Debt, My Problem?

While collections proceedings are taking place and the board is trying to avoid litigation, what happens to the association's other members—the ones in good standing? Since their financial situation could be changed by the costs incurred in litigation, shouldn't they be informed of the problem?

"Every association member has a right to know what the association's financial situation is," say one New Jersey property manager, "But there are limits. Members can know there are delinquencies, but it's against the law to say exactly who it is that's delinquent. The only people allowed to know who's behind in their payments are the people on the board."

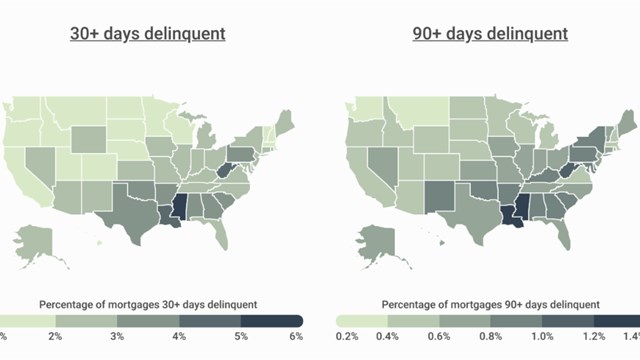

When an owner is behind on his or her monthly fees (and maintenance fees are just as crucial as mortgage payments) the other members of the association do pick up extra slack. The water, electricity, and management costs — just to name a few— must be paid, regardless of whether an owner has gone AWOL for over a month. Other owners share the burden of the non-payer and hope there is a resolution in sight. If the situation gets bad enough—and in the tanking housing market and otherwise shaky economy at the moment, it's happening more and more frequently—the offending association member files for bankruptcy and the HOA loses money.

To avoid this harsh scene, HOAs and their financial advisors must stay on top of their financial statements from month to month. If an owner isn't making his or her monthly payments, it's vital that the association communicates with them to ascertain the nature of the problem and take the all-important first steps to address it. It may also be necessary to create or update the HOA's policy regarding late or missing payments, and to make sure that every resident knows that policy. Adopting a fair and flexible policy for dealing with arrears and ensuring that everyone knows the rules will help guard against the need to ask any community member to "Pay up or else."

Mary Fons is a freelance writer living in Chicago, Illinois.

Leave a Comment