Despite the best intentions of board members, residents, and even managers, co-op and condominium properties don’t always run like well-tuned machines. Sometimes they hit a bump in the road...and sometimes they break down completely. The reasons behind such a breakdown can come from many directions, including financial missteps, physical plant problems, and interpersonal disputes.

Money and Maintenance

In any business, money is always a potentially huge problem—and co-op corporations and condominium associations are no exception to this rule. Financial complications tend to come from two directions: One is financing, the other is reserves.

Financing tends to be the larger potential problem for co-ops, where there is usually an underlying permanent mortgage on the entire property that must be paid monthly. That said, there are condominium associations that undertake community-wide financing for any number of reasons that can make the whole community liable in the event of default.

Reserves (or the lack thereof) are the other area where co-op and condo properties may find themselves in financial distress. Like just about everything else, physical plants and common elements age—and if proper reserves have not been built up and maintained, buildings may find themselves in the financial weeds if a major physical component like a roof or boiler suddenly needs repair or replacement, or if a bad winter or other unforeseen event causes extensive damage to the property.

According to Stuart Halper, vice president of Impact Management, a co-op and condo management firm with offices in Manhattan, Westchester, and Long Island, “A distressed property is generally the result of fiscal mismanagement. For example, boards may choose to undertake the wrong projects at the wrong time. They may decide they prefer to renovate the lobby when in fact they should be upgrading their boiler. Or they may decide to put in solar panels when they should be converting from oil to gas.” And those aren’t just theoretical, Halper is quick to note. “These are real examples that we’ve encountered over the years.”

Nick Ruccolo, a vice president with Crowninshield, a real estate management firm in Massachusetts, also sees financial mismanagement as the underlying cause of distress for condominium communities. “The problem we most typically run across,” he says, “especially with new accounts, is deferred maintenance. Many items that should have been done have been deferred, or passed along. They didn’t start as emergency items, but over time they became emergency items. Typically then, a large assessment will have to be put in place to take care of it. We had a situation like this where all the roofs—and the common roads—of a community were so neglected, they had to be done at the same time.”

Even without an emergency rearing its head, buildings age, and mechanical systems and equipment become obsolete. It’s a fact of life for property owners and managers and can be predicted to a certain degree if community administrators understand the concept of depreciation and earmark funds accordingly. It is the responsibility of a co-op or condo board and its management to properly prepare for the necessary maintenance and ultimate replacement of building systems. A board that consistently defers regular maintenance or opts for a cheap fix rather than a more long-term solution will ultimately land the property in distress. Like a bridge that hasn’t been properly maintained, the overall physical plant could come close to collapse, literally and figuratively.

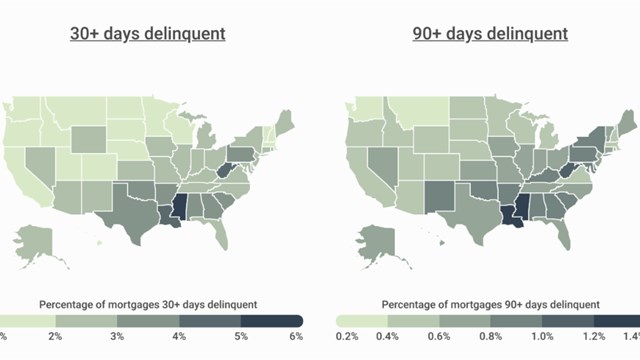

Mortgages

Less common these days, but a very serious problem during the Great Recession a few years ago, was co-op buildings defaulting on payments for their permanent underlying mortgages. As a reminder: co-op corporations own their properties as fee simple estates, and as such can—and do—place large mortgages known as underlying permanent mortgages on their buildings. The debt service on these mortgages is paid monthly and pro-rated among the shareholders. In certain cases—if there are large numbers of subtenants or vacant units, for example, and the primary shareholders aren’t paying their monthly maintenance charges on time (or at all)—the board may not be able to meet its obligations under the mortgage. After 90 days, the lender will place the mortgage in default and begin the process of foreclosure. If the property is foreclosed, the co-op will be wiped out—and all shareholders will lose their equity.

Halper explains that the key to avoiding such a problem is to limit the number of subtenants in the property, which can help keep shareholders committed to their investment. He says it’s also advisable to contact your lender in the event a serious financial or cash-flow problem presents itself to head off a default and foreclosure action. The last thing the bank wants is the property.

Interpersonal Conflict

While perhaps less obvious at first than financial or physical breakdowns, a breakdown in interpersonal cohesiveness, often characterized by conflict between individuals or groups within the community, can be just as detrimental to the health of a co-op or condo. The inability for a board to make decisions due to conflict or constant infighting among different factions within their community can grind the effective operations and management to a halt.

“Interpersonal problems between residents and the board, between board members, and between groups of residents happens all the time,” says Ruccolo. “You have to play the role of conciliator, to get the opposing sides to reach compromise. It’s not unlike the politics of today. You have to find common ground, and that’s really hard to do.”

Halper mentions situations wherein an individual person can get control of the board and will try to run the building or association like their own personal fiefdom. That kind of inappropriate, self-serving control can lead to a complete breakdown in communication, which in turn can make a manager’s job nearly impossible.

The Reality of Managing a Troubled Property

“There are so many challenges,” says Cynthia Petrenko, the principal of Complete Property Management in Vernon, New Jersey. “You ask yourself, can I do it? I’m an extremely small management company and love challenges—I look at things in a positive manner. I study them, and I contact the municipality to see if there are any issues, inspections that failed, and other possibilities, and I meet several times with the board. Then I start with the problems and issues, one by one. I contact their auditor if there is one—some of these properties don’t have an annual audit, and sometimes there aren’t any viable financials at all. Then I review the entire situation. I contact an attorney if I need their help, then schedule a meeting with the community. I tell them the way it is, the truth—the whole truth—even if it isn’t what anyone wants to hear. Quite possibly, a special assessment will be charged to them because of the financial issues. I let any yelling and disparagement roll off my shoulders, then I go to work wholeheartedly. It sometimes takes several years, but it gets done. I try not to burn bridges. The reward is that you accomplish something very hard and you look back, smile, and wait for the next one.”

Avoiding Trouble—and When to Walk Away

A financial pitfall can be dodged if caught early enough, before the dollar amounts involved creep too high for the individual shareholders or owners to handle. “Completing a regularly scheduled reserve study, and maintaining both the reserves required therein and completing the work required as scheduled, will avoid the possibility of the property becoming distressed,” says Ruccolo.

Halper agrees, and adds that “The key is to keep up with both financial and maintenance needs. Raise maintenance annually to keep up with increases in operating expenses and other costs. Cheapness is at the heart of the problem.”

And sometimes, a board’s inability—or unwillingness—to handle its business forces their management company to cut ties and leave the community to its own devices. To illustrate his point, Halper relates a real-life crisis from a former client community. “We had a situation where a board employed a non-union super at a very low wage,” he says. “Eventually they fired him, but it wasn’t done properly, and he filed a wage claim against them. [The board] refused to listen to any of our advice, and we left shortly thereafter because the situation became untenable. We didn’t want to face possible liability with them.” Halper says that while management firms carry errors and omission insurance, there’s still liability, and most firms will part company with a truly dysfunctional board before they become liable for the board’s mismanagement.

“This is tough, really tough,” says Petrenko. “Even when you work for a very long time on a problem, you may find yourself so overly stressed or have a board that is in disagreement with not only you, but each other, that you walk away—and in truth, I have walked away. But regardless, you shouldn’t burn the bridge. You never know when paths may cross again.”

Petrenko, Ruccolo, and Halper all point out that the management business can be stressful enough as it is—managing even one chronically distressed property can add to that stress and can take time away from other properties in one’s portfolio. “You don’t find firms that only handle distressed properties,” says Ruccolo. Partly for the reasons already mentioned, but furthermore, Halper continues, it’s a matter of reputation. Nobody wants to be known as the company whose portfolio of properties is riddled with problems, lurching from one crisis to the next. “It’s a small business, and everyone knows each other,” he says. “You have to be careful of your reputation.”

A J Sidransky is a staff writer/reporter for The New Jersey Cooperator, and a published novelist.

Leave a Comment