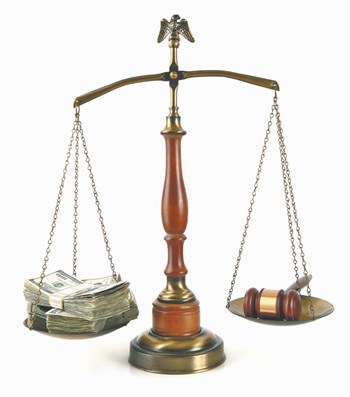

Turn on daytime television and you might get a false impression that people like to go before a judge to work out their differences. There are so many cookie-cutter court shows like where they make the process look simple and quick. The truth is, however, that going to court is expensive, often very time-consuming, and more complicated than it appears on television (although to be fair, those who air out their differences on the tube usually get a stipend.) Filing a lawsuit in the context of a condo association is also a recipe for acrimony between neighbors, board members, and management, and should really be considered as the last resort in problem solving.

Arbitration vs. Mediation

Even in the most harmonious of associations, problems can arise, either between neighbors, between residents and board, or resident-versus-management.

“Owner-versus-board is the most common ADR dynamic,” says Philip Alampi of TAP Property Management in Glen Ridge. “It happens because in the late 1980s, many of the condominium complexes in New Jersey were being built so quickly that attorneys were using documents [for new developments] that other attorneys had used for other developments without really understanding the project that was being built. Because they used boilerplate information, sometimes the information was not as exact as it could or should have been—and that left many things open to interpretation.”

Those loopholes and vagaries can make for rough waters when one person (a board member perhaps) interprets a rule differently than a resident owner, and argument ensues. Fortunately, arbitration and mediation can help settle disputes while avoiding the courtroom entirely.

What’s the difference, you ask? The American Arbitration Association (AAA) differentiates between the two like this on their website (www.adr.org): “Arbitration is the submission of a dispute to one or more impartial persons (known as ‘neutrals’) for a final and binding decision, known as an ‘award.’ Awards are made in writing and are generally final and binding on the parties in the case. Mediation, on the other hand, is a process in which an impartial third party facilitates communication and negotiation and promotes voluntary decision-making by the parties to the dispute.”

According to Alampi, mediation is really the name of the game. “Mediation used to be just a sit-down-and-talk, whereas arbitration was considered binding. They have become essentially the same in New Jersey, since mediation tends to happen all along the way, usually with the manager mediating between two homeowners.”

Anti-Lawsuit Legislation

Alternative dispute resolution has been gaining popularity in recent years as an effective problem-solving method, with one reason being the sheer number of court cases glutting the system. In New Jersey, the state’s Condominium Act requires that boards offer mediation as an alternative before the feuding residents or resident and board head to court. “You never go to court without going to arbitration first,” says Alampi, and mediation happens “as soon as it is requested by either party.”

“There is a federal law, the Federal Arbitration Act, and each state has an arbitration law which create a federal and state policy favoring arbitration to resolve disputes,” adds Eric P. Tuchmann, general counsel and corporate secretary of the AAA. “Arbitration and mediation agreements are generally contractual in nature, however, and except for court-annexed arbitration and mediation programs, they are processes that are not required under state or federal law.”

According to Laurence J. Cutler, an attorney with Cutler Townsend Tomaio & Newmark LLP in Morristown, ADR is a much quicker process than litigation. In addition, he says, ADR is a much less and less costly, “and provides more ease of resolution, as opposed to going to court.”

According to the New Jersey Association of Professional Mediators (www.njapm.org), “The role of the mediator and an attorney are very different. The mediator functions as a neutral that facilitates an agreement between the parties,” and adds that “by law in New Jersey, an attorney may represent only one party to a dispute.”

Putting ADR to Work

According to Alampi, the top points of conflict requiring ADR in buildings are generally neighbor-versus-neighbor disputes, which then morph into neighbor-versus-board arguments. For example, an upstairs unit owner may be making too much noise and the downstairs neighbor contacts the board, who then has to enforce the house rules and proprietary lease items involving noise—thus the noise problem becomes a problem with the upstairs neighbor and the board.

Ideally, the problem-solving process should start with the property manager doing what he or she can to diffuse the situation, and examine underlying problems. The above noise dispute, for example, might be because the upstairs neighbor has inadequate carpet coverage, or possibly because the subfloor and floor have become detached. Perhaps mutually agreeable compromises can be made, such as the upstairs neighbor can only play their music until 7 p.m., instead of the 9 p.m. house rule.

If this approach is unsuccessful, a letter of complaint will be sent from the board to the person against whom the complaint is being made. “A mediator should be brought in as soon as it appears as though the parties will not be able to resolve the disputes among them through direct negotiations,” says Tuchmann. “However, a mediator can be brought in at any time after a dispute has arisen, including after a demand for arbitration has been filed, or even after a litigation has been commenced.”

Finding a Mediator

The ADR process is a confidential one, allowing parties to speak freely about what is bothering them. Crucial to the process’s success is a skilled mediator who can use an array of techniques to help them to negotiate an agreement.

Selecting a mediator is the clearly the first step. There are several ways to select an arbitrator or mediator, says Alampi. “Boards that are having difficulties can get a list of people their manager would recommend as arbitrators. Sometimes they want an attorney, sometimes they want a contractor, and sometimes they want a manager. If the conflict is between homeowners, it is usually good to have a manager [mediate] because we are familiar with governing documents and how to read them.”

“The parties are free to select whomever they think would most effectively resolve the dispute among them,” adds Tuchmann. “Frequently—but not always—mediators are selected who have some background in the subject matter of the dispute. So in the case of a dispute involving a co-operative or condominium, the parties may want a mediator with a real estate background. If there are legal issues in disputes, there may be a particular interest in having a lawyer serve as the mediator.”

To find a mediator and start the process rolling, any party or parties to a dispute may voluntarily initiate a mediation under the auspices of the AAA or work with a private ADR provider.

The New Jersey chapter of the Community Associations Institute (CAI-NJ) offers ADR services to both members and non-members. According to the group’s website, “ADR is offered to community associations and is available to resident homeowners, board members, associations, property managers, and builder/developers. CAI-NJ mediators are individuals who have been trained by the state of New Jersey Office of Dispute Resolution in mediation skills thorough an educational program specifically developed by CAI-NJ.”

CAI-NJ charges members a $250 filing fee for mediation services, and non-members $350. Upon receipt of the ADR Request Form available on CAI-NJ’s website, the organization will send a list of trained mediators to the disagreeing parties.

Through the AAA, there is no filing fee to initiate a mediation or to request the AAA to invite parties to mediate. The cost of mediation is based on the hourly mediation rate published on the mediator’s AAA profile. This rate covers both mediator compensation and an allocated portion for the AAA’s services. All expenses for the mediation—including required traveling and other expenses or charges of the mediator— are borne equally by the parties unless they agree otherwise. The expenses of participants for either side are paid by the party requesting the attendance of those participants. Private mediation companies may charge differently.

The Process

Once engaged, the mediator reaches out to the parties independently or together to learn more about the subject of the dispute. In some cases, the mediator requests brief written positions from the parties. The next step is for the actual mediation to take place.

“The parties and their lawyers, if they have any, come together to present their positions and views to the mediator,” says Tuchmann. “Most mediations take place with the mediator meeting separately with each side in a process know as ‘caucusing.”’ During the caucus, each side can speak on a confidential basis with the mediator. The mediator’s job is to take what he or she has learned about the case and the parties’ respective views and to facilitate a mutually agreeable resolution that each side can agree upon.”

The parties can then continue from mediation to arbitration. “Arbitration is an informal judicial hearing where the parties at odds with one another meet before an arbitrator who hears their arguments, and makes a judgment similar to what the judge would say in a courtroom,” says Wendell Smith, senior partner at Greenbaum Rowe Smith Davis LLP in Woodbridge and the lead author of the New Jersey Condo and Community Association law. “The decision from the arbitrator is binding. Non-binding arbitration is when the arbitrator makes a decision that isn’t binding, but if it’s not appealed within 45 days, it becomes binding.”

The entire mediation process is meant to be quick. “If the parties can’t agree within two to four hours, it’s probable that they won’t,” says Smith.

It’s always in the best interest to resolve any conflicts with neighbor and neighbor or neighbor and board members as soon as possible, through clear communication. Like any argument, the more it sits and isn’t solved, the more it begins to fester and cause tension among tenants. That tension then starts to mount between other residents and the possible solution begins to become more expensive. Letting owners and association administrators know that alternative dispute resolution is available could help to calm the situation down and get it solved before it gets out of control. It’s giving the disagreeing parties their ‘day in court’ without actually having to step into one.

Lisa Iannucci is a freelance writer and author living in Poughkeepsie, New York.

10 Comments

Leave a Comment