CHP (combined heat and power) is a marriage of electric generation and thermal power—the use of an engine, usually gas-fueled, to simultaneously generate electricity and heat. It can be done on a grand scale, as in manufacturing, hospitals and residential districts—or less massively, in condominium developments. As successive generations of systems emerge, CHP has become a leading option for lowering condo expenses. CHP generators are small—lean, green, and smart—but they take a big whack out of energy costs.

“It is one of the few systems of equipment you can buy where you throw a little money at it, and never worry about it again,” says Gregory Hilton, maintenance supervisor at Regency Park Condominiums in Brookline, Massachusetts. “They’re just that phenomenal. I’d recommend it to anyone and everyone.” He is a veteran of two facilities with CHP setups from Aegis Energy Systems in Holyoke, Massachusetts.

Reflective Energy Solutions in Hackensack, New Jersey, helps condo managers find the right system for their needs. “CHP captures the heat that is created, and usually lost, in the conversion from gas or fossil fuels into electricity,” says Aaron Liberman, RES vice president. “If you have a building that needs heat or steam … to heat hot water, then your overall efficiency can be 85 percent, because it (CHP) is throwing off so much heat.” That’s a significant improvement—by 40 to 50 percent—over conventional systems.

Cogeneration works well with single-metered setups to an energy provider, in which entire usage flows through one meter. An association may elect to submeter its system, so that individual tenants pay their fair share to the association. Or, it can include the costs within the association fee, leaving residents out of the billing process, he says.

CHP is all about re-use. While the electricity grid and cogeneration systems produce about equally, CHP is still cheaper by comparison. “Those two horses are running neck and neck,” Liberman says, “but there’s a tremendous amount of line loss between generation source and final customer. If (your system) is self-generating, it’s right there. So that’s more efficient right away. The difference is in the recycling of wasted heat to extend power capacity and cut costs. If you’re able to capture the heat, you’re getting remarkably better efficiency. Your overall energy bill goes down 40 to 50 percent, depending on how much heat you’re capturing and using.”

That’s huge. Several New Jersey multifamily properties have taken advantage of co-gen technology, including Coppergate House, a 150 unit apartment building in East Orange that was built in the 1970s and faced double-digit increases in its energy costs.

The senior housing complex also had an aging inefficient boiler, which property manager Ray Marzulli, sought to replace.

The association contracted with Massachusetts-based American DG Energy, which conducted an energy audit to determine the feasibility of installing a cogeneration system. “I was seeking an effective strategy to both lower my energy costs and replace my older boiler system,” said Marzulli.

The audit determined that installing a cogeneration unit onsite was the best way for Coppergate House to realize significant energy savings without the burden of maintaining the equipment. American DG Energy installed a CM75 cogeneration module on the premises while also upgrading the piping and heating controls for the domestic hot water infrastructure. This relegated the old boiler system as the backup instead of being the primary heating system.

“With American DG’s on-site utility, we’re saving 15% on our electricity costs. It adds up to thousands of dollars in savings annually,” stated Marzulli.

Other New Jersey-based CHP’s are the Kingsley Arms in Asbury Park, Cedar Grove Manor in Cedar Grove, Elm Court in East Brunswick, the Executive House Apartments and Brookside Senior Residences in East Orange, the Oakwood Plaza apartments in Elizabeth, Blair House Condominium in Hackensack, the Country Club Towers in Clifton, Grandview Terrace and Summit Plaza in Jersey City, the Seaview Condominiums in Longport, the Bel Aire Tower Apartments, the Clinton Hill Community Gardens and Zion Towers and Carmel Towers, all in Newark, the Jackson Slater Apartments in Paterson, the Navesink House in Red Bank, and Trent Center Senior Living in Trenton.

The government—through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)—encourages installing CHP for senior housing and similar multifamily housing developments. With roughly two-thirds of the energy produced in traditional power systems lost in heat generation, CHP provides a way to recycle waste energy into thermal power, increasing efficiency from the standard 33 percent to a whopping 80 percent.

HUD’s website describes CHP well: “Instead of buying all the building’s electricity from a utility company, and separately purchasing fuel for its heating (mechanical) equipment, most—or even all—of the electricity and heat can be produced for less money by a small on-site power plant, operating at a higher combined efficiency. The (system) … uses a device that contains an engine, similar to that found in a car or truck, or a microturbine (compact gas turbine generator) that drives a generator to produce electricity. The thermal energy produced by this process is recovered and used to produce hot water or steam, operate a chiller or serve as a desiccant.”

Clean and Efficient

Mike Early, an energy engineer with HUD, calls CHP “efficient, clean, and viable. It provides an advantage by preserving the use of natural resources,” he says. Early recommends that condo associations consult HUD’s website, and call for more specific considerations.

Cogeneration is an inexpensive source of heat for a swimming pool, cooling unit, or building. These systems may not provide 100 percent of a customer’s energy needs, but they take over a significant portion of the utility setup, save considerable amounts of money and re-use formerly wasted energy—three big pluses.

Another consideration: Being off the power grid, CHP systems keep going when power failures hit, which led the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to support them as well. “CHP reduces the emission of greenhouse gases, which contribute to global climate change,” the EPA states. Its CHP Partnership has helped install more than 520 CHP projects, representing 5,118 megawatts of capacity.

“Utility companies want you to switch to systems such as cogeneration because if they can reduce the peak demand of energy that they supply, they will not have to build more power stations,” explains Allan Samuels, managing partner of Energy Squared, an energy design consultant firm in North Brunswick, New Jersey, an affiliate company of Kipcon, Inc.

“This is why the state provides incentives; it is cheaper for them to pay you than to build new power stations.”

Liberman, of Reflective Energy Solutions, advises consulting experts first.

“There’s no such thing as going into cogeneration blindly,” he cautions. “Getting expert help is crucial in finding the right fit and the right cost for your system. CHP is expensive to install, and doesn’t make sense for all users, so an expert opinion can save thousands of dollars.”

RES operates in Washington, D.C., and 15 states, primarily in the Northeast. There are about a hundred electricity and gas suppliers in the nation, and RES works with half of them, choosing carefully. RES helps condo managers select the best source for their needs. “If you want to do something about your energy bill, you can buy cheaper (fuel or electricity) through procurement services; use less energy by upgrading equipment; or you can generate power on-site. Solar power and cogeneration are the most common ways to do that,” says Liberman.

“It’s a very expensive business. So you have to do very careful analysis first to be sure you’re going to get a return on investment. I’ve been involved with projects where they never got their money back,” says Samuels. “You have to do an analysis to be sure you’re going to be using that waste heat you recover through CHP. That’s really, really important.”

Since cogeneration increases the system’s efficiency 40 to 50 percent, results are swift, for mid- to large-sized developments. “Payback generally starts at around 250 units,” Liberman says. “Less than that, and it would not make sense—unless one lives in a place like Florida, packed with people, condos and steamy heat, with an overwhelming need for help.” While RES accepts facilities that spend upwards of $100,000 annually, its average customer spends around $320,000 a year in energy costs—hospitals, care centers, and factories or office buildings.

“A 12-unit building is not even close to warranting the expense,” he says. A condominium with as few as 150 units might qualify, though, if it has a heated pool.

CHP efficiency is based on the size of the unit—and they’re expensive, so some users install a smaller system to cover critical energy areas. They can cost up to $400,000 before incentives. Government and industry paybacks do help reduce costs, by as much as 20 percent off the top.

Will It Work for You?

At what point does CHP make sense for condominiums? “It doesn’t necessarily relate to the number of condo units,” says Dale Desmarais, sales manager at Aegis Energy Services, which engineers, manufactures and installs modular, natural gas-fueled CHP systems. Desmarais considers 100 BTUs the basic threshold at which cogeneration begins to make economic sense for condominiums. “The larger factor is the thermal load—how much heat energy the building uses. CHP is not a backup or primary system; we run in conjunction with an existing boiler system and the existing electricity facility. CHP supplies the base load and utilities supply the peak.” How? By lowering peak demand, on which utility-supplied electricity rates are based. “Peak charges are much higher, and you’re billed all month on that rate,” Desmarais says.

“The decision to go with cogeneration is purely an economical decision. Like all other energy saving measures,” says Samuels, “it’s about the economics. If a building can save money by going with cogeneration, then it’s going to make good sense and be a good decision. But if they can’t then they’re not going to do it.”

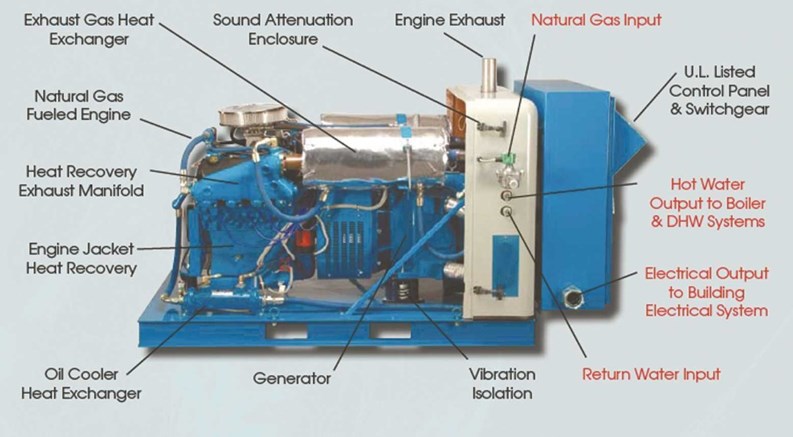

A traditional, central station power plant typically discharges heat produced through power generation into rivers and harbors. “In contrast, there are multiple heat recovery systems in combined heat and power systems,” Desmarais says. “One fuel source, in this case, natural gas, thus produces two sources of energy: heat and electricity. An engine turns a generator that creates electricity for a building, and all the resulting heat is recovered via circulating water.”

A cogeneration system will work for buildings that have a large demand for heat, whether for space heating, domestic hot water, or even for absorption chillers, which is a chemical process that uses heat to produce air conditioning, Samuels explains. “You have to be sure that you are recovering most of the produced heat, which is not always an easy task for a residential building,” he says.

Since condo associations might initially hesitate at the cost, there are leasing and shared savings plans to make cogeneration attainable.

In an outright purchase, Desmarais says, condominiums can expect a capital cost of $200,000 to $300,000 per machine, depending upon the building’s power systems, and where the CHP unit is being installed. Some applications may require more than one CHP unit. It’s not a blind purchase, as Aegis starts with an energy analysis based on readings from the condo’s energy use. Payback is typically three to five years.

Under a shared savings plan, Aegis installs the system with no capital outlay costs by the condominium, and they purchase discounted energy from the Aegis-owned system. The installation is depreciated over the years. “After 10 years,” Desmarais says, “they can purchase it for 30 percent of its original market value.” With a comprehensive maintenance plan, the system basically has what he calls an “infinite life.”

Ann Connery Frantz is a Massachusetts-based freelance writer. Managing Editor Debra A. Estock contributed to this article.

Leave a Comment