COVID-19 has caused more far-ranging, persistent anxiety than any other event in recent history. It has affected our jobs, our living situations, and the way we interact with others, and it’s not done with us yet. Scientists and public health experts are still refining their understanding of the way the virus spreads, but one thing they have determined for certain is that the novel coronavirus spreads through the air—especially within enclosed spaces—and does so far more easily indoors than outdoors or via surface contact.

“Outside is better than inside” has become a refrain among health experts. Depending on the climate where we live and the time of year, most of us can go outside safely on most days. We can maintain social distancing to provide protection from infection. We can wear a mask. But what happens when the weather is just too hot, or air quality too poor, for outdoor activities or open windows? And what about now, as we enter the winter season with temperatures dropping and rain and snow impeding our time to safely open windows and stay outdoors? Among the seemingly endless questions we all have about the virus is how it behaves in more or less enclosed spaces when heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) equipment is running to either heat or cool those spaces.

HVAC and COVID-19

Transmission of the novel coronavirus is thought to happen mainly through large droplets expelled from a carrier’s mouth and nose during coughing, sneezing, or talking. Evidence also suggests that at least some cases of COVID-19 occur via airborne transmission. That happens when virus particles contained in smaller droplets don’t quickly settle out and fall to the ground within six feet of the carrier who expelled them, and instead hang in the air and drift around on currents—posing a threat to anyone who happens to walk through one of those currents. Airborne transmission is thought to have been a factor in the coronavirus’s spread among members of a vocal choir in Washington state, through an apartment building in Hong Kong, and in a restaurant in Wuhan, China.

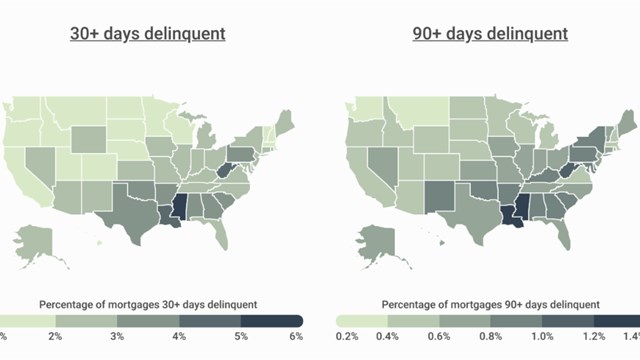

Drawing on what we know about how tuberculosis—another deadly airborne disease—is spread, Dr. Edward Nardel, an infectious disease expert affiliated with Harvard University, suggested recently in an interview for The Harvard Gazette that air conditioning use across the southern U.S. may well be a factor in that region’s surge of COVID-19 cases over the summer. But while expert consensus is that HVAC equipment does have the capacity to spread the virus, questions of what exactly to do about that remain. What precautions can we take to protect ourselves?

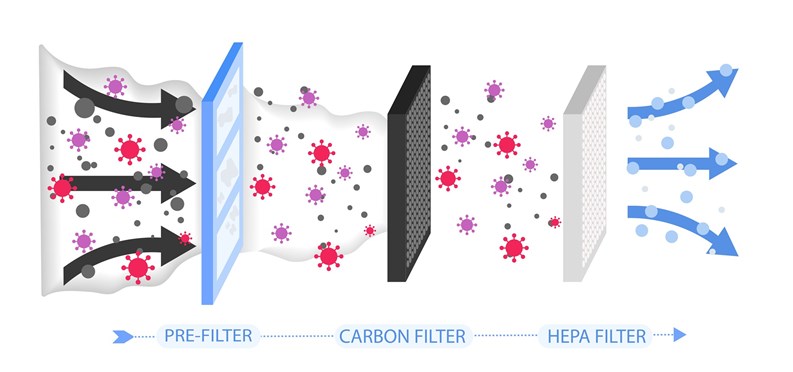

One facts-based option to make heating and air conditioning systems safer is to use high-efficiency filters to essentially strain dangerous contaminants out of the air before they get to anyone’s lungs. Peter Catapano, a mechanical engineer with O & S Associates, a national engineering firm based in Hackensack, New Jersey, says the answer lies in high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, an existing technology currently used in all kinds of medical facilities to filter out many bacterial, fungal, and viral particles.

HEPA technology is beneficial in both common areas and private apartment settings where HVAC systems are active—basically anywhere a large filtration system uses ducts to move air from place to place. As to individual window or through-wall air conditioning units, there doesn’t appear to be any consensus at this time on how—or even whether—they help spread COVID-19. That said, common sense would indicate that if a person or persons were carrying the virus, and were congregated in an enclosed room cooled by an individual unit, the circulating air currents could potentially propel viral bodies around the space, making it more likely that someone would inhale them and themselves become infected.

UV vs. COVID

Nardel also suggests in the same article that ultraviolet (UV) lights—which have been used for decades to sterilize the air of tuberculosis bacteria—could be used against the coronavirus. Catapano agrees, but with some caveats. “Scientifically, and through testing, ultraviolet light does kill the virus if properly administered,” he says. But unfortunately, “[o]ne of the hazards of UV is that it’s also detrimental to humans. It causes skin cancer, and can cause blindness, and it also causes plastic substances to deteriorate. However, it’s been tested and documented that if properly applied for a specific period of time, it will destroy the virus.”

William T. Payne, a mechanical engineer also with O & S Associates, adds that “UV has been widely used in healthcare and hospitals for a long time. It’s a tried-and-true technology, but there is a debate as to whether or not anyone should be exposed to that light—whether the building has to be empty or not [during treatment]. So, running it at night in common areas when no one is around could be an answer to this question, but I would say absolutely that it’s a viable technology to consider when seeking to kill the virus on surfaces.”

Considerations Beyond COVID

While technologies and treatments for COVID-19 are of course foremost in everyone’s mind these days, there’s much more to be considered when evaluating the quality of air and ventilation in your building. In the end, the most important factor for all air quality questions is ventilation—how air moves around the building. To a great extent, the analysis and remediation required for proper ventilation depend on the type of building, as well as its age, size, and design. Prewar buildings are generally ventilated by windows and courtyards, for example, while post-war high-rise buildings benefit from advances in technology that usually include mechanical ventilation systems within the building core.

According to Payne, “Prewar and lower to mid-rise buildings fall into two categories: You have mechanical ventilation, or you have ventilation by typical courtyards. Even way back when these properties were built, there was a [building] code… that said if you have open windows, they account for some amount of ventilation. Over the decades these codes have gotten more and more complicated. In newer buildings, we have mechanical ventilation—which, by the way, gives us more options dealing with contaminants like the COVID virus.”

When it comes to air and ventilation systems in multifamily buildings, among the most common complaints is the traveling, lingering smells of cigarette smoke and cooking odors. “If you smell cigarette or marijuana smoke, or cooking odors,” says Payne, “that tells you that your building isn’t breathing properly. Which means theoretically that you may have a greater concern about COVID-19 as well, because air isn’t being properly exchanged or exhausted.”

To achieve proper air exchange, Payne explains, your building should be slightly positively pressurized, meaning there should be more fresh air coming in than leaving. “If you look at apartment buildings that have mechanical ventilation, their systems are taking fresh air from the roof to the basement, and pressurizing the building, typically pushing air under the apartment doors. That means you shouldn’t use a towel or other device to reduce that draft—you need that under-door airflow. That air is then exhausted through roof fans, or some other type of equipment through the kitchens and bathrooms. If you’re smelling someone else’s cooking smells, that means that there’s a problem with the pressurization balance of the building.”

This problem can be managed, Payne continues. “The first strategy for dealing with smoke and cooking smells is making sure that your building pressurization is correct—that you have proper positive pressure from the corridors into the apartment. After you solve that problem, technologies such as charcoal filters and other products that are known to absorb odors can be put to use.”

At the end of the day, however, when dealing with air quality and ventilation problems, the first and probably most efficient method is to eliminate the source of the problem in the first place. That’s easier said than done, of course. If you have a problem like mold, that’s easy—find the leak that’s letting moisture accumulate, and get rid of it. Then clean up the mold, dry out and disinfect the problem area, and you should be good to go. That strategy doesn’t work on smokers, however—or on viruses. You also can’t remove people who have contracted COVID.

“Source control really only applies to certain conditions,” Payne explains. So for the moment, in the midst of the COVID crisis, the answer may not be limited to simply improving ventilation. Buildings must develop aggressive policies to keep their property’s ventilation systems in top mechanical shape, while making special consideration for keeping the community safe from COVID-19 as well.

A J Sidransky is a staff writer/reporter for The New Jersey Cooperator, and is a published novelist.

Leave a Comment