The majority of co-op and condo residents pay their monthly maintenance fees on time and in full with no problem. The recent recession, however, changed the picture drastically for residents who found themselves laid off, under-employed, or with reduced work hours and could not afford to keep up with the payments. Even absent a major national economic upheaval, other life changes. such as an illness, divorce, or death of a loved one—can also cause unit owners to fall behind.

What’s interesting is that every few years the main reasons for being delinquent on maintenance fees seem to change,” says Ralph C. Ruocco, Esq., an attorney with the law firm of Glazer & Associates, P.A. in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. “Recently, I have seen unit owners on fixed incomes struggling to pay monthly assessments that are naturally increasing due to the increase in the cost of living.”

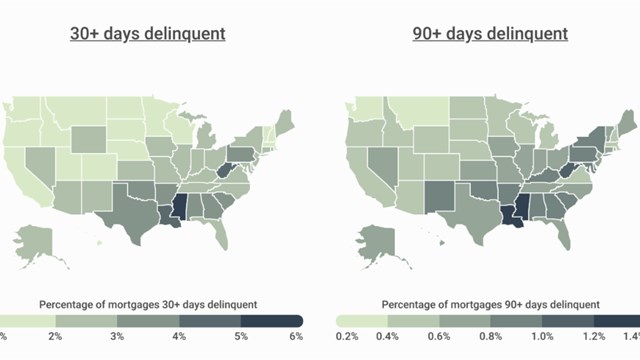

Ruocco says that some unit owners who do not pay fall into arrears because they're already past the point of foreclosure proceedings and are simply in a waiting game. “They're upside-down on their mortgages and are simply living out their final months in the community assessment-free,” he says. “While it varies in severity, if you show me a random community of over 50 units, odds are that their receivables are in the thousands of dollars - and more likely the tens of thousands.”

The Domino Effect

When in tough financial straits, most condo owners will pay their mortgage first, believing that their condo building or homeowners association does not have the ability to foreclose on their home. Actually, says Ruocco, “They could not be more misguided. In fact, if you have to make a choice between paying your mortgage or your association fees, you should pay your association. Association foreclosures are much faster, and definitely have fewer defenses available. Essentially, if you hold title and you do not pay your assessments, you can lose your home.”

“If a person has a hardship situation, such as becoming unemployed, for example, a board has discretion to offer a repayment plan that allows an owner to pay his or her arrears over time,” says Stephen M. Lasser, a managing partner with Lasser Law Group PLLC in New York City. “However, any such payment plan should require the owner to pay current charges as well as a portion of his or her arrears balance, so that the balance becomes smaller each month.” The repayment plan can also waive late fees or interest on the back end, subject to all payments being timely made under the agreement.“This provides the delinquent owner with a financial incentive and benefit to follow his or her repayment plan strictly,” says Lasser.

Generally, however, the experts agree that liens and foreclosure are the last resort. Initiating formal legal action is expensive, time consuming, and makes for bad blood between neighbors. Many managing agents, accountants, and attorneys advocate taking a more cooperative route to getting a delinquent association member back on track.

A lien is a legal claim against property that must be satisfied when the property is sold. As a result of the payment problems, the homeowners association would place a lien against the individual's unit. When the homeowner sells that unit, the proceeds from the sale are used to pay off the debt and any court costs.

In cases where arrears coincide with a unit owner's declaration of bankruptcy, the situation changes a bit yet again. According to attorney Stuart J. Lieberman a founding shareholder of the Princeton-based law firm Lieberman & Blecher, PC, “In most cases, associations have a right under the Condominium Act to file a lien in situations where property owners are delinquent on their monthly assessments. However, in the case of bankruptcy there is an automatic stay pursuant to Section 362 of the Bankruptcy Code, which appears to preclude the association from filing a lien representing the delinquent account. Specifically, once a bankruptcy petition is filed, most legal actions taken against the petitioner are put on hold. This is referred to by lawyers as an ‘automatic stay.’ The effect of the automatic stay is that the bankrupt estate remains status quo, so that the bankruptcy court can work things out, and either allow for reorganization or liquidation of the estate.”

Lieberman goes on to say that “Among other things, the automatic stay precludes any act to create, perfect or enforce a lien against the property of the estate or the property of the debtor to the extent the lien secures a pre-petition claim. It therefore seems that the prudent and legally appropriate response is to not file a lien against a unit owner who has filed for bankruptcy.”

Lieberman stresses that “This does not mean that the association has no remedies available to it once bankruptcy has been filed. The association will be a creditor in the bankruptcy case and will file a claim in the bankruptcy proceeding.”

Legal Recourse

Accountants are rarely involved in this process. As auditors, accountants leave that job to the attorneys. Their role is to make sure management charges late fees, and does so according to policy.

It didn’t matter that Mr. Smith was able to scrape enough money together each month to pay his mortgage. Without that repayment plan, not paying his maintenance fees is still grounds for eviction. “When a co-op shareholder defaults on maintenance payments, the co-op can evict the shareholder and also require the shareholder’s lender to pay the maintenance arrears,” Lasser says, “or the co-op can conduct a UCC sale of the shareholder’s stock and lease and wipe out the lender’s lien against the stock and lease securing the lender’s mortgage loan. In theory, a co-op would be worse off as a result of multiple arrears, because co-op owners jointly pay real estate taxes, as well as any underlying mortgage encumbering their building, so their finances are more interdependent than condominium owners.”

If the unit owner had owned a condo, the situation changes. “A first mortgage has priority over a condo association’s lien for unpaid common charges,” says Lasser. “In these situations, a condo board can conduct a sheriff sale of the condo unit if it's not owner-occupied, or complete a lien foreclosure of the unit. A condo board cannot begin an eviction proceeding against a unit owner until the unit owner’s interest in a unit is extinguished via a sheriff sale or foreclosure sale.”

David L. Ferullo, CPA, a senior audit partner with the Curchin Group in Red Bank, agrees. "A lien doesn't get the association more cash right away, but they should be able to recover some of the money later," says Ferullo. "It will depend if the market value of the unit exceeds the current mortgage."

While Lasser says that multiple arrears are more common in condos than co-ops because the collection methods available to co-ops are more effective, and their pre-purchase screening process more rigorous, multiple arrears adversely affect both types of community. “If there is not sufficient cushion in the building’s budget, ultimately the other owners will face maintenance increases to make up the shortfall. The impact of non-paying owners is usually felt more severely in buildings with fewer apartments.”

Foreclosure Action

“If a unit owner is upside down on their mortgage, the association stands to get the property back at a foreclosure sale, only to see the mortgagee take the property from the association,” says Ruocco. As previously mentioned, “Association foreclosures are typically much faster than mortgage foreclosures. Our clients have been successful in beating the banks to the punch, and then renting the unit until the bank finally gets around to taking the unit back from the association.” While the association may not recover all that is owed, getting rental revenue from a contested unit in arrears can help stop some of the bleeding.

When going after a unit owner to recoup the charges, the law firm must follow the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), a federal statute that regulates the behavior and practices of debt collectors.“A law firm is bound by the FDCPA,” says Ruocco. Individual states may also have statutes spelling out—or limiting—how and by what means an association can recoup arrears.

Many management companies send residents in arrears a stern letter or two before turning the case over to legal counsel in hopes that the threat of getting an attorney involved will compel the delinquent owners pay up. “The role of the association’s attorney is to collect the outstanding amounts owed to the association,” says Ruocco. “There is a statutory process that needs to be followed by the attorney which includes an intent to lien letter, a claim of lien and accompanying intent to foreclose letter, and ultimately a foreclosure action. The association’s attorney may be in contact with the delinquent owners and be the go-between between them and the board in order to stop the process and enter into a reasonable agreement acceptable to both parties.”

An effective collection attorney is also there to diffuse a potential problem with an owner. “They may not be paying simply because they are unhappy about something as simple as trash collection, or some other community issue,” says Ruocco. “When an owner hears certain truths from their association’s attorney, it tends to resonate more,” which can have an almost miraculous effect on a formerly recalcitrant resident.

The bottom line is just that: the bottom line. Monthly common charges need to be paid in order to ensure that the building and its amenities are kept accessible and in good repair, reserves are funded, and that any minor repairs can be covered without leveling assessments on everyone. Not only do the residents need to keep on top of their payments, but boards and management companies need to be diligent in collection and, if necessary, take the actions they need to take—including foreclosure—to insure the future financial solvency of their community.

Lisa Iannucci is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The New Jersey Cooperator.

Comments

Leave a Comment