It's bound to happen eventually: calamity befalls your condominium development in the form of windstorm damage, fire, personal injury or the like. The first step most associations take is to call the insurance company and file a claim. However, there are times when it might be better not to file a claim when an incident occurs.

How Insurers View Claims

It's commonly understood that community associations in which numerous claims have been filed often pay more in premiums than those with spotless pasts.

The reason for this is not that a certain type of claim scares insurance companies but more so an association's lack of attention or responsibility to their property will cause insurance carriers to consider raising the premium or even not renewing the policy, warns Alan Geisenheimer, CIC, president of the Geisenheimer Agency in Fairlawn.

"Lack of attention to snow and ice removal is probably king in this area," he says. "[Another example is] allowing swimming in a pool that is either not attended or posted that it is not guarded."

Another no-no for associations would be not controlling who uses the recreational amenities, or failing to set limits on how they are used. If the association turns a blind eye to wild parties thrown in common areas for example, the insurance company will not look favorably on any claims ensuing from this desertion of responsibility.

Associations might also fail to set controls for the use of their private streets. Precautions such as speed bumps, speed limit signs and caution signs for road hazards go a long way to making the insurance carrier comfortable with the way an association runs its day-to-day business.

Insurance companies are least likely to complain about claims that stem from incidents not under the association's control. An example of this would be if a fire were started by a lightning strike—an incident no good property manager or board member could have possibly prevented.

"Carriers are very concerned with multiple water claims, because that could lead to an inherent problem with a building," adds Joel Meskin, Esq., vice president of McGowan & Company, Inc., insurance underwriters in Fairview Park, Ohio. "Water claims tend to be a kiss of death."

"There is no set amount for a premium adjustment after a claim," says Geisenheimer, who has specialized in insuring condos, co-ops, homeowners associations and apartments for 35 years. "And there is no set amount of reduction for a claim-free year. If you have a good track record, your premium was probably 'credited,' which means reduced. Subsequent to several losses or one major loss, you may lose some or all of those credits."

Basically, buildings without numerous claims are a better risk for insurance companies, Geisenheimer explains, and since the company stands a better chance to make money on the risk, they will offer preferred pricing.

Meskin, who has written numerous articles on insurance-related topics, says that it's difficult to say how much premiums go up after one incident, since there are so many variables that come into play in order to answer this question. Especially in the case of bodily injury claims, carriers might look at human factors, like who the property management company is, whether the company has recently changed, or whether a new board has recently taken over.

"Most carriers look at two things: frequency and severity," Meskin explains. "These are the two gauges to the impact. Many carriers will have a threshold at what they will look at in the initial instance and what they will consider to non-renew."

Meskin goes on to say that "each carrier has its own philosophy and method of evaluating - some go solely by statistics and do not get into a case-by-case basis, assuming that it is a law of diminishing returns to do so. Others will look at risks on a case-by-case basis and try to underwrite around the claims."

Meskin reminds his readers that they need to remember that the insurance company, like any other company, is in the business of making money. They're driven by statistics, and by actuaries whose job it is to determine what it takes to make a profit.

"Most people think that carriers make an outrageous amount of money, but they in fact work on very small margins and pay out significant amounts," Meskin explains. "As an underwriter, I must be able to look the insurer in the face and indicate they will make money by writing a risk and by writing it at the recommended price."

The Claims Process

In the event of an incident, the insurance carrier will expect you to report a claim as quickly as reasonably possible if you want to have coverage, says Geisenheimer, whose agency is licensed in over 25 states and has written insurance coverage internationally. After that, the insurance company will determine how the process will be handled—if it should be defended, contested or settled and for how much.

"Most carriers have claims analysts, claims guidelines and lots of experience in knowing the value of damages and how best to resolve it," Meskin reports.

The adjuster will evaluate the claim differently depending on whether the claim is a property or physical damage loss or a liability loss.

Meskin explains that "on the property side, the adjuster will evaluate the loss and determine based on the market value or replacement cost what the damage is to either make the insured whole or to pay the actual cash value of something (which is the replacement cost, less depreciation). On the liability side, it is a function of injuries or damages."

After the claim is evaluated by the carrier's adjuster or analyst, a resolution will be offered to the association. If they reject the resolution, the matter will be handled by way of either dispute resolution or a lawsuit.

As far as compensation and/or damages go on the property side, the insurance company will evaluate the costs of rebuilding or repairing the damage. Some questions they might ask include the following: Do the people living in the building need to be relocated? Will an architect have to draw plans? Is there a need for scaffolding for a high-rise to make the repairs?

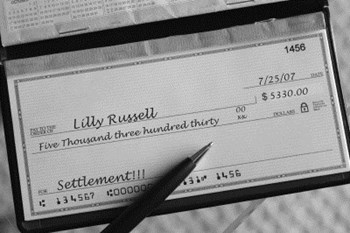

When it comes to claims dealing with physical injuries sustained on your HOA's property, "It might be considered more an art than a science," says Geisenheimer. "Consideration is given to pain and suffering and the desire to actually present a reasonably fair settlement to avoid going to court, where most insurance companies do not fare very well."

Is it Ever Better to Settle?

When an incident happens that requires repair or replacement, those who handle the claims on behalf of the building—usually the property manager, if there is one, or someone from the association's directors or board of managers—will evaluate the problem.

The question might arise: "Would it be better just to pay for damages out of the association's reserve funds to avoid a premium hike?" Maybe—but is such a move acceptable to insurance companies? Is it legal? Piekarsky, whose practice frequently represents community associations, stresses that the greatest reason associations should steer clear of paying out of pocket for incidents that they could otherwise file with their insurance carrier is the potential expense of doing so.

In Meskin's eyes, "'Better' is in the eye of the beholder."

Meskin suggests that associations carry large deductibles—like $10,000 or $20,000—so that they do not need to file a claim unless significant damages occur. Most associations can handle this type of loss, and a larger deductible can actually motivate them to manage their properties better, he says.

"I look at insurance as catastrophic, while many look at it as part of the operating fund," he explains. "It may be better for the association or condo not to claim an incident and instead pay out of a reserve fund. But the board must fully understand the potential consequences of such an action. I once saw an association make the decision to handle something itself and it got out of hand and turned into a $500,000 defense fee bill."

Piekarsky has heard of a case where the association cleared up its own problem without filing with their carrier and everything worked out okay. This particular North Jersey association had such a bad history of incidents that their premium was up to almost $200,000.

"They wanted to do anything and everything to get it down, and they were erring on the side of resolving things on their own—not reporting them, but rather just paying defense counsel to defend them," he relates.

However, Piekarsky ultimately agrees with Meskin when it comes to cautioning associations about this kind of approach. He knows of another association that decided to just get their defense counsel to defend the incident and not report it in fear of a skyrocketing premium. In this case, however, the counsel fees became even more staggering than the premium would have been and —as Piekarsky says—it probably would have been more cost-effective to report it to the carrier.

"When you report a claim, usually the carrier assigns insurance defense counsel," he explains. "They pay for the cost of the defense. In many cases, the greatest exposure is your defense cost, not the risk of verdict or what you're going to settle the case for, but what ultimately you'll end up paying on the case. At the end of the day, the settlement or verdict may be minimal compared to what you spent defending it through your lawyer and expert fees."

He also cautions association boards to be aware of what their fiduciary responsibilities are—they may be depleting reserves that should not be used for paying for costs associated with incidents not reported to the insurance carrier.

All the professionals agree that associations should be wary when trying to handle claims themselves. If they feel they can settle a claim themselves and then it goes too far without settlement, they'll have to file a 'late notice' claim with the insurance company if they still want to file.

"Under that scenario, if the insurance company was damaged in their defense by the late notice, they may hand the claim back to the association without an obligation to either defend or pay," warns Geisenheimer. "Another problem with late notice to the insurance company is if the association has abrogated the reasonable defense that the insurance company would have had."

For example, the association may already have admitted guilt and liability to the injured party, which would make it extremely difficult for the insurance company to fight the claim on the association's behalf.

In general, Geisenheimer cautions against an association not claiming an incident and paying for damages themselves. He calls it "playing with fire."

And when you play with fire, it's no secret that you can really get burned.

Domini Hedderman is a freelance writer and aspiring novelist living in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Leave a Comment