In any association of two or more parties, clear communication is essential to ensure a mutually beneficial relationship. In an HOA, there are interlocking relationships, such as between the board and the manager, and between the board/management company and the resident shareholders/unit owners. For the average resident, especially those new to co-op or condo living, it’s not always apparent who in the community is responsible for what, and who they can turn to turn to for answers to their questions.

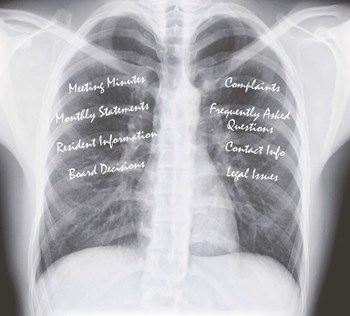

Part of the necessary flow of communication is the exchange of information contained in the governing documents and community records. Such records detail the community’s financial status; legal proceedings; and correspondence between the board, unit owners and management company. Some of the information is off-limits to all but the board members, the property management staff, and the board’s legal counsel.

The disclosure of other community records is required by state law, as well as by the association’s bylaws. The idea is to allow all residents to keep an eye on the actions of their neighborhood representatives, who may be making decisions that will take money from all of the residents’ wallets. Part of working towards clear communication in a community is making the effort to ensure that everyone understands the rules, so that homeowners don’t have unrealistic expectations about what data is available for inspection.

Knowing what’s allowable will enable board members to make prudent decisions about what information they should regularly disclose, and what they should let out on a case-by-case basis. It also will help the board to avoid the knee-jerk reaction of clamming up and stonewalling when a resident of residents lawfully demand certain community records.

Which Open Records?

Respect for the privacy of fellow residents is important, but privacy concerns must be balanced by a thorough understanding by the board and residents of what records should be made legally available to residents. The board also must understand what information needs to be disclosed to the community, and how often such information should be disseminated.

Generally, there is a requirement for a board and management company to be transparent in their operations, says Gregory M. Dyer, Esq., a partner and community association law specialist with McCarter & English LLP, in Newark. “There are requirements that board meetings be open to attendance by unit owners. The schedule of the meetings should be communicated to unit owners so they can attend,” Dyer says, noting that the New Jersey Condo Act, and the Planned Real Estate Development Full Disclosure Act require these actions. “Minutes of board meetings must be kept, and must be available for inspection by unit owners,” he says.

Financial records also must be open for inspection by unit owners, says Dyer. He advises that other records also should be open for inspection. “If it’s become part of the association record, they should make [the records] available,” he says.

It is against New Jersey state law to not disclose the annual report and tax return on a corporation; copies of minutes also are required to be available in many communities, and contracts can sometimes also be public information. According to David L. Ferullo, a senior audit partner with The Curchin Group, an accounting firm in Red Bank, under the state’s sunshine laws or Open Records Act, if it’s public information, it has to be available. Getting the records sought, though, must be done in the right way—no demands or pushiness over the phone or in person are needed. A resident first must request the records clearly in writing in a letter to the board/management company, and the records should be made available to the resident.

But some records should not be divulged, in any instance. Some things that the board discusses in closed session—such as compensation, personnel issues, litigation, and delinquencies—should not be divulged to residents.

“Anything that people could come back and sue you for disclosing should not be disclosed,” Ferullo says. It’s a delicate balance however, since disclosing some of this information will help the board to protect itself from a lawsuit, because by divulging information that could be criticized, or litigated later, the board shows its openness. Potential conflicts of interest also can be revealed through financial records, since those records detail related-party transactions, such as when a board member’s company is hired for a project.

Transparency with community records serves a few purposes. It creates goodwill among the residents; it protects the board and community from potential litigation; and it can help to reveal potential problems by allowing others to scrutinize the board’s actions.

Who Discloses?

Some boards err on the side of caution, withholding information when residents should have access to it. Consistent or stubborn stonewalling could invite a lawsuit, but the opposite behavior by the board also could lead to trouble. Some boards want to publicly post records of maintenance delinquencies, as a way to shame residents in arrears into paying. Such behavior could land board members in court, since it’s unfair to post that information—not to mention illegal.

According to state law, board members are entitled to see any document pertaining to the management of the building. Residents who are not serving on the board are not allowed to see all of those documents. Often the treasurer will have closest access to financial records, and the secretary will have closest access to the other building records.

In smaller co-op buildings, records sometimes are kept in a board member’s file cabinet. In such cases, the board secretary often will handle the building documents, and store them in his apartment. Larger buildings hire property managers to store and maintain the building’s records in their office. Managers are not, technically speaking, in control of the records, and do not determine who should see those records. Management companies are subject to the dictates of the board, which in some cases, at their discretion, can allow others to see building records.

In order to do their jobs, certain professional consultants for the community are given access to the records. According to Richard Siegler, a partner with the law firm Stroock & Stroock & Lavan, LLP, which has offices in New York, L.A., and Miami, accountants for the community will have access to its records, since they need the records to correctly do their jobs. For construction projects in the community, architects and engineers also will be given access to records such as blueprints.

Shareholders should have access to the minutes of shareholders meetings, but they usually won’t be allowed to see the minutes of board meetings. Attorneys for a would-be buyer of a unit sometimes are given access to shareholder meeting minutes before the buyer closes on the unit.

“The site manager is not the one who should be divulging information to a unit owner,” Ferullo says. “The board should direct the management company to disseminate that information, if they want it done. They can even put it in the newsletter.”

For some boards, divulging information such as meeting minutes is a regular task, done monthly. Others send out such records less frequently, such as biannually.

One potential records problem to consider is the possibility of the total loss of the community’s records through a fire or some other disaster, Ferullo notes. “They should have a disaster program in place so they have a backup of records,” he says. “If a board doesn’t have a disaster plan, we advise them to get one.”

When in Doubt…

When a board is in doubt about what records it should divulge, board members should always consult their management company and the board’s attorney. Board members also want to take care to observe the community’s incorporating documents and bylaws when judging what information to make public. Those documents always require that an annual audit be done of the community’s finances, and in some cases, it’s required that a hard copy of that audit be sent to unit owners. If not, the owners are entitled to see the document by inspecting it in person.

In addition to being able to inspect the annual audit of the community’s finances, residents also must be allowed to inspect financial receipts of the community. But again, delinquencies are one of the exceptions to that rule.

“Boards should not be disclosing to others who the unit owners are that are in arrears with their fees,” Dyer says. “We would advise them not to do that, since they may open themselves to liability.”

Jonathan Barnes is a frequent contributor to The New Jersey Cooperator and other publications.

Leave a Comment