Co-op or condo ownership can mean fewer concerns about maintenance and administration for residents, but it also means living by a new set of rules and regulations. Co-op and HOA boards don’t operate as little fiefdoms unto themselves, of course—but the truth is that your board has a significant degree of power to decide on policies and procedures for the entire association community.

Most of the time, boards and their managers run associations smoothly and without incident. Troubles only arise in the system when the actions of the board run against the overall interest of the community, or when one or more neighbors dispute a board’s action, believing it to be unfair. Such cases can lead to lawsuits, with neighbor suing neighbor and the courts ultimately sorting out the disputes.

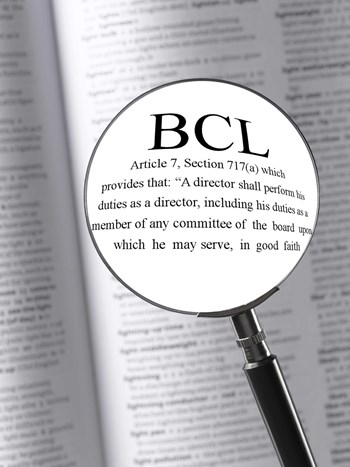

These cases are governed by the business judgment rule, which came out of court decisions based on the state’s Business Corporation Law (BCL). The business judgment rule is one of the primary statutes regulating operation of cooperative housing corporations in New Jersey and other states. The business judgment rule essentially says that if the board or a board member acts in good faith in making a decision in the interest of the building or association, the court will likely not intervene, even if the decision turns out to negatively impact the building or association. Courts have consistently ruled that board members have been given the power to make such decisions for their co-op, and partly because of this, they cannot be held personally liable for those decisions.

Business Corporation Law Sets Bar

Courts refer to the business judgment rule when determining whether or not the actions of a board or board member are permissible under the law and under the governing documents of the cooperative in question. The rule is used regularly in other states, as well as in New Jersey. New Jersey’s BCL was implemented more than a century ago, and has been updated as business practices have changed, technologically speaking and otherwise. The state’s Business Corporation Law originally was the most open and business-friendly law in the nation.

“Delaware passed a general corporation law in 1899, and even before that in 1890, there were New Jersey laws regarding what a corporation could do,” says Edward A. Berman, an attorney and managing member with Berman, Record, Sauter & Jardim, which has offices in Morristown and New York City. “In 1868, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that corporations were not citizens, but entities with power only conferred on them by the legislature.”

In other words, corporations are entities, not people, and are subject to the law. Community association boards are elected and charged with promoting and preserving the property of the association, Berman says. “As a board, they are called upon to make decisions much like corporate officers would do,” he says.

“Business Corporation Law governs the way a co-op corporation can act,” adds Dennis Estis, an attorney with Iselin-based Greenbaum Rowe Smith & Davis, LLP and the co-author of the New Jersey Condominium and Community Association Law Book, published by Gann Law Books. “They are subject to the business corporation act of New Jersey. If they’re not in compliance with that, their [decisions] are not going to hold up in court.”

The BJR and Board Decisions

The business judgment rule essentially protects the business decisions of a co-op’s board of directors, explains Hubert C. Cutolo, an attorney with his own firm in Manalapan. That protection of the board of directors’ decisions is based on the fact that the court won’t overturn a reasonable decision, and based on the fact that you can’t successfully sue board members based on a reasonable decision they made. “Reasonable” means the board of directors exercised their duties in good faith, he adds.

“Most board members are not an expert on board operations—as long as they use reasonable business judgment, they’re fine,” Cutolo says. “They do have an obligation to do due diligence. Typically, the board will use business judgment by consulting professionals, such as accountants, lawyers, and property managers.”

The only time the business judgment rule comes into play with regards to a co-op is if the board is challenged in a decision it made, Cutolo says. Such an instance can happen when a board authorizes a special or emergency assessment, which is usually a collection of extra money to be used for some physical improvements in the community. “Oftentimes the board is challenged when owners have to pay more money,” he says.

Boards also are challenged over election issues, such as when a group of residents believes a board election was not fair. “It’s a pretty regular standard; a lot of courts are using the business judgment rule to determine the reasonableness of a court’s action,” says Kim Borek, an attorney and the owner of Borek & Associates, LLC, located in Princeton.

Upholding Boards’ Decisions

A lawsuit challenging the merits of a board’s decision is not an everyday thing in New Jersey, but the state Supreme Court decided just such a case back in 2007. In July 2007, the state Supreme Court issued its ruling in the precendent-setting case of Committee for a Better Twin Rivers vs. Twin Rivers Homeowners’ Association. The court overturned an Appellate Court’s decision and found that community associations could lawfully impose reasonable restrictions on their members, such as restricting the posting of political signs. The court also found that such restrictions do not violate the New Jersey Constitution’s protections regarding freedom of expression and equal protection.

The association board’s complaint in the Twin Rivers case centered around the question of whether the association had effectively replaced the role of the municipality, and if so, whether the association’s rules and regulations should be subject to the free speech and free association clauses of the New Jersey Constitution. One part of the complaint intended to nullify the association’s policy regarding the posting of signs in the condo development.

The association’s policy stipulated that residents could post a sign in any window of their residence and outside the flower beds, provided the sign was no more than three feet from the residence. Only one sign per window and per lawn was allowed. The intent of the sign policy was to avoid the clutter of numerous signs and to maintain the aesthetic value of the common areas, as well as to allow for leaf collection and lawn work.

“At issue in Twin Rivers was the question of whether the New Jersey Constitution’s speech and assembly clauses should be applied to limit the authority of homeowners’ associations to promulgate certain community-wide restrictions and, if so, under what circumstances,” says attorney Jonathan H. Katz. Katz, who is with the New Jersey law firm of Sterns & Weinroth, where he advises condominium associations, cooperatives and homeowners associations.

“In the Supreme Court’s decision, the court determined that even in light of New Jersey’s broad interpretation of its constitutional free speech provisions, the ‘nature, purposes, and primary use of Twin Rivers property is for private purposes and does not favor a finding that the association’s rules and regulations violated plaintiffs’ constitutional rights.’ Moreover, the court found the plaintiffs’ expressional activities are not unreasonably restricted by the association’s rules and regulations. Finally, the court held that ‘the minor restrictions on plaintiffs’ expressional activities are not unreasonable or oppressive, and the association is not acting as a municipality.’”

Avoiding Un-Neighborly Conflicts

They say you can’t fight city hall, but it may be just as tough to fight the board. Courts in New Jersey are inclined to allow boards to make the decisions they need to for their communities however they see fit, with the obvious exception of decisions not made in good faith. Clear conflicts of interest, such as if a board member tried to hire himself or his wife’s company for a job, are easy to spot. But more subtle abuses of power are harder to detect, define and fight. Even the appearance of bias on the part of a board while making an important decision may well lead to a resident filing a lawsuit against the board, so it’s best to avoid even the appearance of bias.

People join their community’s board for a variety of reasons, and sometimes those reasons are less than noble. Board members, though, must be careful to stay within the bounds of the law when making decisions for the community, experts say.

“In every contract they enter into, in every decision they make, they have to be aware of the responsibility they have,” Berman says.

Jonathan Barnes is a Pittsburgh freelancer and a frequent contributor to The New Jersey Cooperator.

Leave a Comment