One of the trickier problems to deal with when you live in a co-op or condo is dealing with board members who sometimes let the power go to their heads. Even though they are entrusted with a great deal of responsibility in the smooth running of the building, it’s vital that board members don’t use their position to create a situation where they are setting themselves up for a conflict of interest dispute.

“Conflicts can arise in all facets of association management,” says Bonnie Bertan, president of Association Advisors, a property management company in Freehold. “Typically the conflict would arise at the board and management level. This is in large part because the management company is typically responsible to bid services and the board makes the hiring decisions directly. There are cases where the conflict could extend to committees such as a procurement committee.”

Nothing undermines a community’s faith in their leadership faster than things like impropriety and self-dealing amongst the board/management team, or even the implication that these things might be going on.

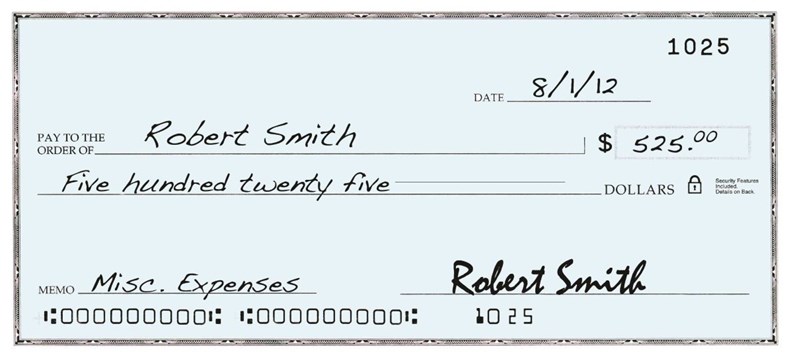

“If a management company has painting contracts or landscaping contracts or janitorial services in which they are a principal owner and hires one of these companies without disclosing that they have ownership or a stake in them, that’s a conflict of interest,” says Jim Evans, CPM, and president of the Institute of Real Estate Management (IREM). “From the board standpoint it’s the same thing. Often we get a brother, sister, uncle or whomever that are in that business and they push to have them added to the list without disclosing their relationship.”

In these cases, the board member stands to profit financially from mixing his or her two interests and may be tempted to put the interests of the business ahead of the interests of the building. When that happens, the board member runs the risk of breaching his or her fiduciary obligation to the building.

Avoiding Problems

Living in close proximity to others, along with a sense of loss of control, gives rise to a whole host of different types of disputes. Adding a conflict of interest problem into the mix can make the situation even more volatile. Common sources of conflicts of interest are directors and management companies who directly or indirectly are connected to companies that the association may currently use or consider hiring.

Some board members try to get away with having pets in a no pet building, having jobs done for free (such as landscaping) in exchange for hiring a contractor, or hiring friends or family to do something in the building. Some examples include a board member allowing an unlicensed painter to work in his apartment, approving a sales application that otherwise might not be approved.

“I have a firm policy in my office, any contractor that does business with any of our clients cannot do business with the property management company,” says Evans. “So we can’t get accused of getting our lawns cut for free because we gave the lawn company all of this business.”

Other conflicts of interest are not as obvious as the examples above. Perhaps the association is trying to decide if they wish to pursue a noise violation when the only complainant is a member of the board who lives next door to the accused violator.

In this case, the director with an interest at stake would be best served by disclosing that interest, making his or her case to the board in the same manner any other owner would and then letting the rest of the board vote on the matter.

“You have to set clear and concise policies that directly address conflicts of interest issues,” says Raymond H. Du Bois, treasurer of Essex and Sussex Condominium Association in Spring Lake. “You also have to indoctrinate new board members to make sure that they understand that this is something that you need to stay away from and that the board has a zero tolerance policy on board members who will profit from using certain goods and services.”

New Jersey Condominium & Community Association Law, a book co-authored by attorneys Wendell Smith, Dennis Estis and Christine Li, states that “certain basic principles have been enunciated by the courts in reviewing challenges to an association’s actions: first, that the acts of an association ‘should be properly authorized;’ second, that the association management has a ‘fiduciary relationship to the unit owners, comparable to the obligation that a board of directors of a corporation owes its stockholders,’ and that ‘fraud, self-dealing or unconscionable conduct at the very least should be subject to exposure and relief.’ ”

“An easy way to avoid conflict is to establish a formal written conflict policy,” says Bertan. “The policy should define what constitutes a conflict. Specific examples should be incorporated. The policy should identify the individuals that the policy would apply to such as a board member or the management company. The policy should encourage individuals who are unsure of a potential conflict to discuss this with the board. The board can then determine if this individual should be recused from participating in negotiations in that instance.”

The best rule of thumb for everyone—for the board member, the manager, and the building—is to avoid all situations in which even the appearance of a conflict of interest is present.

“We had a member of our board who was a roofing contractor and we probably should have used him but we didn’t,” says Du Bois. “We never went that way. He was the one that led that effort; he didn’t want to go down that road because it could have led to possible issues.”

Cause and Effect

Conflicts of interest that are either overlooked or allowed to continue can create real damage to community morale as well as to undermine the credibility of the governing board.

To help clients avoid conflict of interest issues, a manager should be conversant in the regulations articulated by New Jersey’s Condominium Act and the Planned Real Estate Development Full Disclosure Act (PREDFDA) which governs condos/HOAs and the Cooperative Recording Act and Business Corporation Law, which deals with co-ops, related to any issues regarding conflicts of interest. As well, the manager must be familiar with the co-op or condo’s documents and bylaws, which also will likely address conflicts of interest.

“In today’s day and age when condos are having so many issues conflict of interest is definitely an issue,” says Evans. “Conflict of interest can be simply avoided if everyone is upfront with all of their abilities and connections and affiliations. This is an ongoing problem and it always needs to be addressed. The board needs to know who their management company is and what they stand for and are not afraid to ask uncomfortable questions like ‘what is this charge for?’ or ‘why did you do this?’ or ‘how come this company always seems to get the bid.’ If it doesn’t pass the smell test it stinks.”

When certain conflicts of interest occur, it’s the community that suffers. As an example, if a management company has a financial interest in a vendor, not only is it hard to be sure that the association is getting the best pricing, but if that vendor is failing from a performance perspective, it is not in the management company’s best interest to recommend a change as they will be losing business.

Family Matters

Let’s say a board member acting in good faith hires a family member to do interior maintenance work in their building and something breaks. This is a serious problem that you are better off not even giving yourself the chance to get in.

“If the management company has a relationship or is related to a service provider then it should be disclosed prior to the bid process,” says Bertan. “Then the board should decide if that type of practice is beneficial or detrimental to their community.”

“We had somebody on the board whose wife was a real estate agent and you could clearly see that the way he was talking about things and the issues he was raising would clearly benefit his wife’s income,” says Du Bois. “You could see in his decision-making that it would be to his wife’s benefit. He had an agenda. He was looking out for himself and not the association.”

Boards would be well-advised to establish clear policies and boundaries to determine where liability would rest and who would compensate the building if damage occurs.

Boards who learn the hard way—either through criticism or in the most extreme cases recall from the board—that hiring a family member or friend was a bad idea from the get-go, often don’t repeat the exercise.

“Good communication will always win out and if you are trying to hide something people will know,” says Evans. “A good management company or board has nothing to hide. You must make sure that you are communicating with the board if you are a management company and vice versa. When that doesn’t happen people get frustrated and something that could have been fixed very, very simply all of a sudden gets blown out of proportion or there’s hurt feelings and the relationship is irreversibly harmed.”

Keith Loria is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The New Jersey Cooperator. Staff Writer Christy Smith-Sloman contributed to this article.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment