Most homeowners love complaining about their property tax bills almost as much as they despise paying them.

The issue is always on the minds of New Jersey's homeowners, and has been for some time. New Jersey has been studying property tax reform for three decades, since the establishment of the Tax Policy Committee under former Governor William T. Cahill in 1972. The idea of a constitutional convention to reform property taxes was first raised in 2000 by then Sen. William E. Schluter.

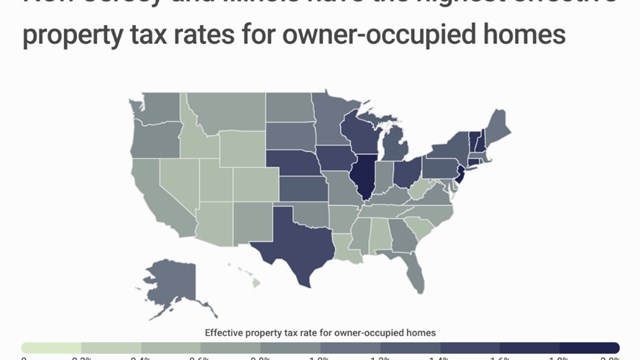

New Jerseyans pay the highest property taxes in the nation. According to Cy Thannikary, the chairman of the Citizens for Property Tax Reform, a coalition of 57 different organizations representing over 500,000 homeowners, 47 percent of all tax revenue paid by the average homeowner comes from state and local property taxes, compared to 30 percent for other state residents. In the last 10 years, the average property tax increased by a whopping 52 percent, he says.

According to George Hawkins, executive director of New Jersey Future, a tax advocacy group, there are two fundamental reasons why taxes in New Jersey are so high. "First," says Hawkins, "New Jersey relies more than most states on local property taxes to pay local service costs. In most states, more of the local service costs are shared across a county, or come from the state itself. In New Jersey the preponderance of those expenses is covered by the local property tax, so it becomes disproportionately high compared to other taxes because it covers a larger degree of expense."

"Another reason contributing to higher local property taxes is that New Jersey has a lot of local governments that need to be covered for expenses—566 municipalities, to be exact—and there are even more school boards than municipalities. All of those have their overhead costs, institutional costs, and administrative costs, which all add up. There certainly is the thought that if more of these expenses were shared among the municipalities, you could save on the expense side. On the tax side, New Jersey relies more on the property tax to cover those expenses."

Before former Governor James McGreevey left office, he signed a bill establishing The Property Tax Convention Task Force, headed by Rutgers University professor Carl Van Horn, and calling for the state to put the issue of having a constitutional convention to a vote of the people. Acting Governor Richard Codey, who is not seeking election this fall, does not have a strong position on the issue.

The task force issued its final report in December 2004, which supported funding some $3.8 million to convene a constitutional convention at Rutgers for the purpose of making recommendations to install a fairer property tax system. "If there is to be a Property Tax Convention, the sole purpose of such a Convention will be strictly limited to considering and making recommendations to reform the current system of property taxation and that these recommendations must further one or more of the following goals: eliminating inequities in the current system of property taxation, especially as they affect low and moderate income residents; ensuring greater uniformity in the application of property taxes; reducing property taxes as a share of the overall public revenue; providing alternatives that reduce the dependence of local governments on property taxes; and providing alternative means, including possible increases in other taxes, of funding local government services," says the report.

Holding Lawmakers Accountable

Unfortunately, says Thannikary, an economist and 21-year New Jersey resident, the report fell on deaf ears again, victimized by the "usual Trenton logjam"among legislators. A5269, a bill introduced by the Majority Leader, Assemblyman Joseph J. Roberts Jr., D-5 in Camden County, recommending a property tax convention passed the Assembly, 45-30-2, in May but stalled in the Senate, which has adjourned for the summer. "The only way that we the people can get any systemic reform is through a property tax reform convention. So my organization, which is called Citizens for a Property Tax Reform, which is a statewide coalition—we have one simple, single mission—and that is to support a property tax reform convention," says Thannikary. "We feel strongly that the only way we can get real reform is to take the process out of Trenton. If we limit it to the legislators—the politicians—it will never happen."

"It's a lot of foot soldiers. It's a grass roots movement. At least when we started it nobody was talking about it. Now at least they have a discussion about it and it's become a campaign issue, which is a plus. Before they never talked about it. But this time we can make them hold their feet to the fire. They have to make a public statement, they have to promise it, and that promise must be kept."

What's Next

Thannikary said the issue will be hotly debated during the upcoming gubernatorial election between Democrat Jon Corzine, currently a U.S. Senator, and Republican Doug Forrester, the ex-mayor of West Windsor and a former Congressional nominee in 2002. Corzine, says Thannikary, has issued a position paper supporting a convention and his four-year-old organization intends to call him on it during the campaign and the election. Forrester also has a plan and ideas on the subject, Thannikary says.

"The next step is to make them accountable for it. It's actually a three-pronged approach: one is to heavily campaign on the gubernatorial election. We need a governor who can stand up for the people rather than giving lip service, and stand up for the people, not for the special interests. So we want to ask both the Republican and Democrat candidate where they stand on the issue," he says.

In 2004, the average homeowner's property tax went up about 7.2 percent, according to Thannikary. And the tax level is a burden for seniors and those on fixed incomes, he says. "What we want is a governor who will promise a constitutional convention and support it."

Giving the Money Back

The issue of property tax rebates also came to the forefront this year during the legislative debates over this year's budget. Acting Governor Codey—who also presides over the Senate— proposed $900 rebates for seniors and disabled citizens, but wanted to cut other rebates to $300 in order to close a budget gap. Senate Democrats backed this plan, but Assembly Democrats have insisted on maintaining full rebates for all citizens and proposed a series of budget cuts and land sales in order to preserve those rebates, which last year totaled $1,200 each for seniors and disabled citizens and $800 for other homeowners.

The situation came to a head on June 29 when the two branches introduced contradicting budgets—resulting in legislative gridlock, and making the Legislature miss its deadline to approve the state's budget.

Governor Codey called the showdown between the two lawmaking bodies "political showmanship" and called for an end to the squabble between Democrats.

"The state budget isn't a game," Governor Codey said of the impasse. "It's a serious matter that affects the lives of every New Jersey resident, and it should be treated that way. The public deserves better than phony numbers and false promises."

A pair of Senate Democrats—Fred Madden of Washington Township in Gloucester County and Stephen Sweeney of Deptford—announced that they wanted rebates fully restored. "Nothing is more important than ensuring our residents get the greatest possible amount of property tax relief," Madden told the Times.

Shifting the Burden

New Jersey residents also pay a hefty school tax. One option being debated is Assembly Bill 40041, which has come to be known as the New Jersey Save Money and Reform Taxes, or SMART Act. Assemblyman Louis Manzo, D-31, says the shift would use a state income tax to fund a portion of the school budget, resulting in significant rebates for homeowners.

"What it basically does is shift about $3.5 billion of the school funding burden from property taxes over to income taxes," Manzo says. "It's a revenue-neutral bill that just shifts the tax burden from one tax to the other tax. We do that because there are twice as many income tax filers in the state as there are property tax filers. So when you put such a large burden on such a small tax base, you end up with the property tax problem we have."

According to Manzo, the bill widens the tax base because income would be generated by Jersey residents who rent, as well as people who commute into the state for work, as opposed to gaining school budgets solely from state homeowners.

"[Property taxes in Jersey are high] because we continue to put the funding of schools mainly on property taxes," Manzo says. "School taxes on average [account for] 55 to 65 percent of a New Jersey property tax bill—so that's the driving factor."

I Want My Rebate

New Jersey has been issuing rebates to homeowners since the 1970s, but the rebate system has come under fire recently for a variety of reasons. Critics argue that the checks no longer represent as high a percentage of tax bills as they used to, the annual amount fluctuates, and there is no guarantee of a rebate.

"They've been on-again, off-again," Manzo says of rebates. "For a period of time, the rebates were suspended. The SMART bill [includes] a second bill which is a constitutional amendment that dedicates the revenue so that the money is collected outside of what is needed for the budget. So you never again face the problem that Trenton is facing this time—how much of the budget is going to go to rebates? With the SMART bill, the money is constantly generated through this pool of funds, so that the budget in Trenton is not dependent on money that's [intended] for rebates."

Manzo says the bill is currently under debate in the Assembly and in the Senate. He is hopeful the bill will be voted on and passed, but acknowledges that it's a big step for lawmakers to take.

"The prospects are good, provided people have the nerve and the courage to implement it," Manzo says. "And I think that's going to come very quickly because I believe the public is going to put so much pressure on legislators to finally do something with this that it will get done." Based on the reaction from his constituents, Manzo expresses confidence that this is a measure people want.

"I campaigned on it in my district, and my opponents in the primary tried to attack the SMART bill," says Manzo, "and I won overwhelmingly. So people understand why you need to shift the burden from property to income."

Manzo says the bill would affect condo and co-op owners equally in proportion to what homeowners pay. In the state, condo owners pay property tax based on the value of their homes. Co-op owners are assessed a fee from their association for their share of the property tax bill. Manzo says his bill would result in rebate checks for condo owners. In a co-op situation, co-op owners would see a reduction of their property tax bill.

Manzo says other ideas have been proposed, but feels that their chances for success are dubious.

"The only other solutions that are being put out there involve hiking sales and nuisance taxes," says Manzo. "Like raising cable bills and taxes on realty transfer fees, and putting taxes on health clubs and hair salons. Those things don't work. They're just as regressive as property taxes. If we're going to look for another source of tax funding, we should look to the most progressive one—and that's our New Jersey income tax." He adds that those other ideas "will put the state in more of a hole, because it winds up being more aggressive, they take more money out of the economy than they put in."

Anthony Stoeckert is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The New Jersey Cooperator.

Leave a Comment