Conventional wisdom holds that if you have to have neighbors, you’re better off living next door to owners than renters. By definition, owners have a stake in their building, and are supposedly better neighbors. They are cleaner, quieter, and friendlier. They keep better hours. Their dogs don’t bark. They pay their bills on time. They are wonderful and amazing in every way.

Tenants, on the other hand, have as they say a “bad rep.” They are drifters. They don’t stay in one place long enough to make nice with the neighbors—probably because they’re on the lam. They play loud, unpleasant music until the wee hours. They are always late with the rent, if they even bother to pay at all. They are mean, rude and selfish. They probably drink too much and their dogs are often unruly and terrify residents and small children.

Obviously, the “common wisdom” isn’t exactly accurate. There are plenty of wonderful tenants, and just as many lousy owners. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t occasional conflict between rental tenants and fully-vested owners in an HOA, often over issues with house rules or conflicts between neighbors.

It’s important for HOA boards and managers to familiarize themselves with what rights and responsibilities tenants have, and to uphold those rights under the law. Because co-ops and condos differ dramatically in how they view those who rent, we’ll examine each one separately.

Cooperative Sublets

First, the co-op. This conventional meaning of a sublessee confuses the term somewhat when it comes to co-op apartments, however. Because co-op shareholders technically, through a proprietary lease, own not the apartment itself, but shares of the cooperative, a tenant of the shareholder is considered a subtenant or the sublessee. If Jane is a shareholder residing in the Top Shelf Towers co-op building, and rents her apartment to Nick, Nick is a subtenant of Jane.

Because Top Shelf Towers is a co-op, Jane has a number of hurdles to jump in order to rent her apartment—Top Shelf Towers may not allow anyone to sublet their apartment at all. At first blush, the prohibition on renting out an apartment you own may seem downright un-American. Doesn’t the Constitution grant right of property? Yes, but a co-op’s governing documents make a different case.

In any case, there are a number of reasons why a co-op may choose to be stingy about subletting.

“Generally, co-ops like to have people living in the building who own the apartments,” explains attorney Steven Wagner, of Wagner Davis P.C. in New York City. “There is a belief—a well-founded one—that people take better care of property they actually own.”

“Some co-op boards rely upon the general conventional wisdom that you don’t want tenants in buildings because they cause more damage,” says David Byrne, a partner with Stark & Stark in Lawrenceville.

Co-ops generally sell for less than comparable condos. The primary reason buyers choose the former is because of the higher rate of owner occupancy, and the degree of safety, cleanliness, and neighborliness that implies.

“An association, whether a co-op or condo association, always feels more comfortable with owners in the building,” says William D. Bierman, a partner with Nowell Amoroso Klein & Bierman in Hackensack. “There’s less of a turnover, more of a community feel in the building.”

That said, as mentioned previously, things are not so black and white. Most co-ops do allow subletting in some carefully regulated fashion. The idea is to protect the owners, not hurt them.

“Some boards allow sublettors, but limit it so that the building can accommodate tenant shareholders who for whatever reason need to lease the apartment, but don’t want to sell or cannot sell,” explains Wagner.

For example, a shareholder may suddenly have to relocate to California, but selling in this economy would mean taking a loss on the property. Subletting would potentially forestall financial ruin.

This business of prohibiting subletting because they might not be good tenants might make co-op boards seem fickle, if not mad with power. Although there are certainly a few Napoleons (or Catherines the Great) on co-op boards, the fact is, there are other, more concrete reasons boards must limit the number of sublettors in a building.

“It has to do with lending,” Wagner says. “A large number of apartments that are not owner-occupied, some banks will look at that and not want to lend.”

The accepted ratio that banks look for is 3:1. If more than a quarter of the apartments in a co-op are sublets, banks will think twice about lending money or even refinancing—especially in the worsening economy.

“It affects the value of apartments if there are too many sublets,” Wagner says. “It could prevent people from refinancing or selling because banks will be reluctant to make a loan.”

Complicating matters, sponsor apartments are included in the 25 percent tally the banks look at—they take up the first available spaces, sort of like legacies at Ivy League schools.

“If the sponsor has 25 percent of the units, and the policy is to freely sublet, that may put the number over 25 percent,” notes Wagner.

In short, a liberal subletting policy could severely limit the financial options of not only the co-op, but the individual shareholders of that co-op.

“Aside from policy issues, there are also individual issues,” says Wagner.

In the case of sublets, co-ops and condos are very different. Co-ops are viewed by lenders as of a piece. Condos are considered the same as unattached houses.

“With a condo, you own it, so you’re not subletting,” says Wagner.

Still, many condo boards vie for greater controls over their properties. They want to both have and eat the cake, in effect, desiring the ease of selling without approval and the ability to approve (or rather to reject) sales.

And that brings us to the more prominent housing arrangement in New Jersey, the condo.

Condo Rentals

As far as renting is concerned, condos are more or less the same as regular single-family dwellings. Unlike a co-op, a condominium in an HOA does not have the right to reject a renter—or to limit the number of overall renters in a complex.

“The condo association can’t tell any owner that he can’t rent,” says Byrne.

There are some restrictions that an HOA can put in place, however, albeit modest ones.

“They could have bylaws that restrict various types of renting,” says Bierman. “You can’t rent for less than six months, or less than a year. You don’t want to turn the building into a hotel.”

Thus, a tenant in a condo answers to the owner, and has little if any interaction with the HOA—unless rules are violated.

“An HOA wouldn’t have to provide any specific services to the tenant,” says Byrne. “They still have a fiduciary responsibility to the owner, but the duty runs to the owner, not the tenant.”

Tenants who contact the HOA when problems arise—unless the problems are of a condo-wide nature—are barking up the wrong tree.

“If a tenant calls and says the refrigerator’s not working, that’s not our problem,” says Byrne.

What can be an HOA’s problem is how the tenant behaves. Often, the owners—who are the landlords of the rented unit, after all—do not reside in the building. Thus, the HOA has to live with whatever issues a tenant might bring up—figuratively and literally.

“A condo association, these are people who live in the building,” says Bierman. “So they experience any problems that they have. The problem is spread out in the building.”

Let’s say a teenaged son of a tenant is vandalizing the lobby. What’s to be done?

“Technically, the association has no jurisdiction over that,” says Bierman. “They have to go through the owner, who may live in Florida, who may live in Arizona. They can call the police, if the tenant is defacing the building, or breaking the law. Otherwise, they have to go through the owner.”

This exposes one aspect of this kind of rental that is peculiar to condos.

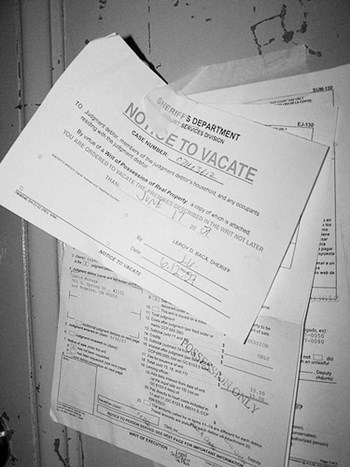

“The association can’t evict a tenant out of its own building,” says Bierman.

A prudent rule to add to existing bylaws is to compel the owner to give a copy of the lease to the HOA.

“Many associations require that owners send copies of the lease, so they know who that person is, what the relationship is,” says Bierman. “For a lot of reasons, including safety.”

Regardless of whether you rent or own, it is important to know the rights of tenants and what to expect, should you personally be renting or subleasing, or renting or subleasing your property. When it comes to conflicts in these scenarios, there is a lot of red tape, so obviously it is best to know the pitfalls of the process, before you get stuck dealing with a miserable landlord, board, or renter.

Greg Olear is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The New Jersey Cooperator.

Comments

Leave a Comment