In markets throughout the nation, 2019 was a year of uncertainty, reflecting change in the basic mechanisms of how we view, buy, and sell real estate. That uncertainty extended to all markets, from traditional single-family homes to co-ops and condominiums, to commercial properties – and the same factors that affected markets in 2019 are expected to continue to reverberate in 2020.

Taxes, Real Estate, and…Taxes

When it comes to home ownership, the conventional wisdom of economists (and the government policy that followed it after World War II) held that appreciation of real estate as the primary asset of middle-class families was the most successful and secure way to build wealth and insure a comfortable retirement – particularly when combined with social security retirement benefits. As a result, and to encourage home purchases and long-term ownership, government at all levels offered benefits to families in the form of tax deductions. The federal government enshrined that approach by providing a deduction for state and local income and real estate taxes against income in federal income tax filings.

Over the decades since the mid-20th century, the evolution of deductible taxes has developed in two main directions, sometimes simultaneously. Some states and municipalities have enacted state and local income taxes, while others – especially at the local level – have levied higher and higher real estate taxes to provide for superior schools and other civil services. These state and local taxes (often abbreviated with the acronym SALT) became an important consideration in home prices, as they had long-term effects on the after-tax cost of home ownership. In most cases, these deductions made homes in high-tax areas more affordable, after tax considerations were calculated in the cost of ownership.

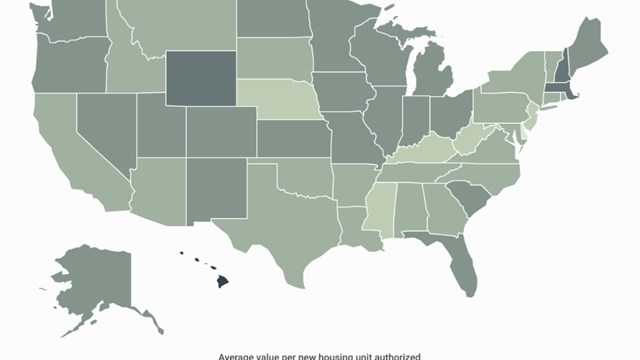

The Tax Cuts & Jobs Act of 2017 changed that. While the new law increased the dollar amount for a standard deduction by doubling it, the change also capped SALT deductions at $10,000 per year for a married couple filing jointly. That cap increased the after-tax cost of home ownership, ultimately depressing or even permanently decreasing values, and therefore prices.

The Reality

Jonathan Miller is the president of Miller-Samuel Inc., a real estate appraisal and consulting firm located in New York. Miller is a national expert on both commercial and residential markets, and publishes annual and quarterly reports for markets throughout the United States including New York, Boston, southeast and western Florida, California, and select markets in Texas and Colorado, among others. According to him, “2019 has been about taxes, especially in New York City and other high tax areas. The change in the SALT deduction that went into effect last year played havoc in the purchase market because it caps deductions at $10,000. It slowed down New York and its suburbs before anywhere else. In general, California tends to run a year behind New York in trends, and we are seeing similar trends pick up there now.”

Sensitivity to Interest Rates

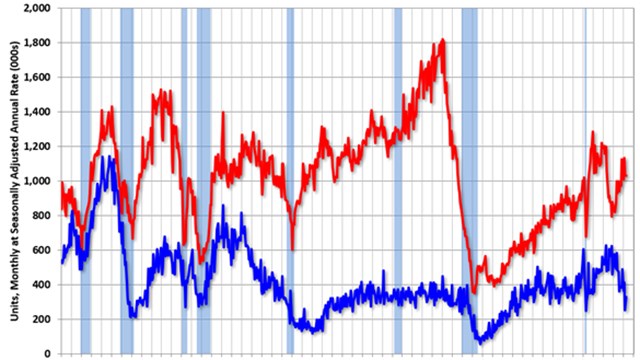

Another major factor in real estate sales markets is the price of money itself. Most buyers (though not all) borrow substantially to purchase a home, especially in the starter market. When interest rates – aka the cost of money – rise, monthly carrying costs become higher. That change in financing cost can depress or inflate a market. When rates fall, buyers can afford more; when they rise, prices inevitably fall.

“Mortgage rates falling a full point over the past year have mitigated damage from the effect of the reduction in SALT deductions,” says Miller. “What’s really important when we look at housing trends is that most people look at prices first, but that’s sort of low-hanging fruit when it comes to trends. One should look at sales activity and inventory first. Offering prices take 12 to 24 months to show a pattern after sales and inventory do their thing. We saw inventory rise in 2018. In 2019, we saw prices begin to slide. In 2020 we will see more of that. But ultimately, the effects of the SALT reductions were skewed by the drop in interest rates for home mortgages. Overall, the situation is not as bad as it could have been.”

The Deepest Cut

The most pronounced change, according to Miller, has come at the top of the market – the so-called luxury sector – in all areas of the nation. In places like New York City and Miami, the top end of the market was overbuilt to begin with, and there was far too much inventory. Many of these units are not moving.

Miller notes that inventory in New York’s Westchester and Fairfield counties are more stable, mostly due to low interest rates, but their high end is still off. The area overall is slowing, and pricing are slipping. Not all segments are showing the same softening, but in the aggregate sales are down and prices are up – though the starter market for first home purchases is still strong due to lower interest rates. Miller believes the overall market will stay like this for a couple of years, unless there is a sudden rise in interest rates, which might cause a short-term burst with buyers getting in to beat the rising rates.

“The bottom line,” says Miller, “is that sellers still haven’t gotten the memo.” They are still clinging to the price they thought they would get a couple years ago. It takes sellers longer than the rest of the market to adjust to new forces and factors.

New Jersey

When it comes to the Garden State, Eugene Cordano, Executive Director of Sales for Halstead, New Jersey says, “We saw, depending on where, less supply overall in the 2019 market, and prices off by about two to three percent. Overall, there were a lot fewer transactions. In the past, what you would have seen with low, low supply is prices going up—but we didn’t see that. We saw what was effectively, the opposite. Why? We have a roaring economy, and low interest rates, but low demand in the New York/New Jersey/Connecticut markets. It’s a result of market lag, the change in tax law which resulted in a cap on deductibility, psychologically, that’s played a significant role.”

Cordano goes on to explain that the SALT deduction changes played a less significant role in the high end of the market, but have been very important in the mid and lower levels. The result is that some sectors of the market where real estate taxes are lower and fall under the $10,000 cap instituted in the new law, have healthier sales levels. Higher tax areas are moving more slowly and are more negatively affected.

Another important and unexpected result of the tax law change is that many sellers, unhappy with the resulting dip in prices have taken their units off the market and are renting them instead. Cordano says the rental market is brisk. As for 2020, he adds, “Who knows? What holds people back are financial constraints in New Jersey: high taxes, high cost of living, etc. But people are here because they want to be here. Right now, the main issues are psychological. Is there value? I don’t know if the market comes back in 2020. Things may not change until after the election, and whatever happens with that. We are in unique times.”

Politics

Non-market considerations are also affecting the housing market. The main concern among investors revolves around what moves the Fed will make, and what will ultimately happen with the China trade war. There is, overall, too much uncertainty. The bond market is already collectively terrified, and while discussing bonds may be the cure for insomnia, the reaction of those markets to political influences has repercussions on the markets that provide financing for real estate purchases.

2019 will likely be remembered as one of tentative change. Investors in both real estate and financial markets are cautiously trying to find their way through a myriad of factors, including the change to our basic tax laws. The early winners appear to be low tax areas with room for growth. The losers appear to be high tax areas that have benefitted from growth and investment during the past cycle. Miller says it’s too early to tell long term, but that 2020 will be a year that reflects the changes already under way, and the ability of investors to react and adjust.

A J Sidransky is a writer/reporter for The New Jersey Cooperator, and a published novelist.

Leave a Comment