Whether it’s a renovation, an emergency repair, or anything in-between, condos, cooperatives, and homeowners’ associations are rarely not spending money on something. And while they may have reserves on hand to pay for its latest project, money often needs to be scraped together pronto in order to cover unexpected expenses, delays, or other issues.

While special assessments to raise needed funds are a common fact of life in multifamily communities, coming up with a hefty amount in a relatively short window of time isn’t always realistic, depending on the means and limitations of individual residents.

An alternative to assessment is to take out a loan from a bank, which the association can then pay back over time — with interest — often by making a marginal increase to residents’ monthly dues. This can often be an appealing option — but it’s important for boards to do their due diligence and weigh the pros and cons of assessment versus borrowing before entering into any long-term financial arrangement.

Why Borrow?

There are a number of reasons why a board might want to take out a loan to fund even a fairly modest project. But realistically, the higher the price tag, the more sense it makes to bring in an outside financier.

“Associations typically borrow money when they have a large capital need, such as a roof, siding, a roadway, or something similar,” explains Lisa Wagner, VP and Business Development Officer with ConnectOne Bank in Englewood, New Jersey. “Existing cash saved in a capital reserve account might be short, or the association might not want to deplete all of those funds, so it will borrow from a bank.”

Jared Tunnell, Senior VP of National Cooperative Bank, which has offices in Virginia, Washington, D.C., New York, Ohio, and Alaska, cites some more examples of big-budget to-dos: “The largest ones that I’ve seen recently, if you’re a townhouse community for example, have been roofs, siding or stucco. For high- or mid-rise buildings, the big line-items are facades, balconies, or HVAC risers.”

A responsible board will be aware of the inevitability of these major repair projects, as everything from building systems to roofs to facades all face gradual wear and tear. “These projects are often necessary 15-20 years into the existence of a property,” notes Charles F. Withee, President and Chief Lending Officer of the Provident Bank, which has locations throughout New England. “Let’s say that you’re faced with repairing or replacing the roof and the siding simultaneously. If the former is going to cost you $200,000 and the latter $300,000, and your association is 100 units, you can do the math on a special assessment. That’s a big nut.”

“The benefit of borrowing...is that you’re actually using the balance sheet of the community to borrow money, so it doesn’t impact an individual resident on a personal level, or affect personal credit,” explains Tunnell. “They’re using the aggregate value of the community to borrow, as opposed to a specific unit. And then you can pass on the monthly fee to the next owner. So if you’re dealing with a 50-year-old community with 50-year-old pipes that need to be replaced, various owners have come and gone who have enjoyed those pipes over that time period. Why should a handful of individuals shoulder the burden of coming up with that replacement money upfront?”

From Whom?! And How?!

Of course, the first step is to identify a qualified lender with which an association can negotiate agreeable terms and come up with a feasible repayment plan. And certain criteria need to be met on the association’s side in order for it to prove a viable lendee.

“The association will need to have a reserve account that is being funded,” says Rachel Rowley, VP-Association Financial Partner with Alliance Association Bank in Oswego, Illinois. “Most associations want to use their reserves so they can take out a lower loan. The reserves are actually what helps them become qualified. Past-due accounts can hinder the loan process. For [us], they can have no more than 10 percent of their total units over 60 days past due. And they should look for a loan that does not contain a prepayment penalty. A bank will not finance a project for longer than the life expectancy of the product – so the board...should look at all of the projects that will need to be undertaken during a specific period of time. If they need their roof taken care of now, but may need siding in two years, it may behoove them to take out a larger loan and complete both projects simultaneously in order to avoid starting the loan process over again a few years later.”

“Most banks, if they are assessing the loan request correctly, will ask for a recent capital reserve study, year-end and interim financials, arrears report, estimates from contractors, and bylaws,” adds Wagner. “We like to see a special assessment put in place by the board for the homeowners to pay the loan. This ensures that the bank will get paid back dollar-for-dollar by the homeowners. If the association has a problem with collecting management or assessment fees, we would be concerned. If the board doesn’t want to share the idea of a loan and/or assessment with its owners, this is concerning; even if the bylaws state that they do not need approval, we would prefer a vote by the residents anyway. It’s not worth a legal battle in the future.”

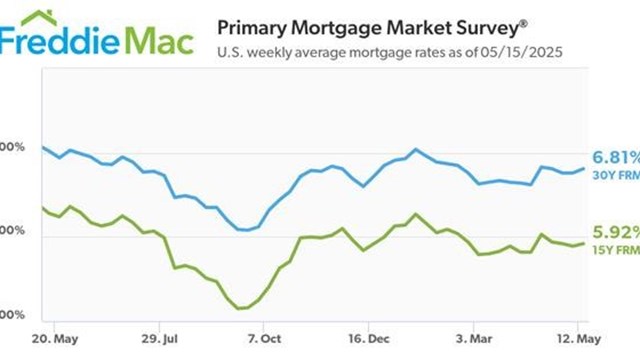

It’s also worthwhile for a board to research banks in the area to ascertain whether one may specialize in association loans. “If you approach a bank, and they ask something like ‘What’s the collateral again?’ then you’re at the wrong bank, because they don’t know that they’re dealing with a cash-flow loan,” warns Withee. “And there are other underwritings to consider; we’re typically dealing with seven-year terms, or possibly 10 years. We calculate for an association what the debt service is going to look like; what they need to do is look at the budget to determine what they’ll need to raise in dues to cover that new debt service.

“From there,” Withee continues, “you need to review the significance of that increase. If it’s going to be a 30 to 40 percent spike to the condo fee, that could be a real problem. The bank is going to look at the likelihood of the unit owners staging an uprising. There’s no magic number to indicate that, but if the increase is north of 10 or 15 percent, we’re going to need to have a discussion. You can write beyond that, certainly, but that’s an area that the board should consider: how this loan will affect the condo fee. And an alternative is to keep the fee untouched, but then you’ll probably have to have an enormous special assessment.”

What, Me Worry?

So it’s imperative that a board consider how much it will have to raise monthly fees in order to pay off its debt in a timely fashion, and whether its residents will reasonably be able to afford to do so month after month. And there are other red flags that may indicate that a board is entering into an ill-advised loan transaction, as well as problems that can turn a loan sour down the line.

“Borrowing is a bad idea if the association is only looking to get a head start on capital projects,” warns Rowley. “In those cases, they should focus on increasing assessments to help them prepare. But an association loan is one of the safest loans that a bank can enter into.”

“[We look at] delinquencies,” adds Tunnell. “How many people are not paying [monthly dues or maintenance] – though we look more at the number of units [in arrears] than the balance owed. We look at investor-owned units or sublets; we like to see a majority owner-occupied. In major metropolitan areas, we like to see this number at around 50 percent.”

“These loans are surprisingly simple for those that do them all the time, on behalf of all parties concerned,” says Withee. “But the converse is also true: if you deal with a local bank – and maybe it’s the bank of the condo president – and they don’t know these things, you’ll have to educate them, and that’s going to be hard for the board. The bank will get uncomfortable, then the board will get uncomfortable. That discomfort, for a traditional commercial bank, is going to result in no collateral, and no tertiary guarantees, which means you essentially have one source of repayment: the condo fees. But that hypothetical bank fails to realize that the source of repayment is actually diversified among 100 or more individuals, and is actually very predictable. We’ve done these loans for a dozen years, and never lost a penny. They’re always good loans. But you don’t want to have to catch your banker up to speed, so don’t get hung up on just using a board member’s favorite commercial banker. Be very objective. Ask how many deals they’ve done, and with whom. Make sure the bank is specifically equipped to do an association loan. Because, while it’s not hard, it is a specialized practice, and your bank needs to be prepared to do it.”

Mike Odenthal is a staff writer/reporter for The New Jersey Cooperator.

Leave a Comment