There is no doubting the wisdom of one of America’s founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin, who wisely said, “In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.”

While Father Time can take care of your mortality, the federal, state and local municipal governments handle your respective tax burden. And, it’s not a surprise that few subjects get people more riled up than paying their taxes. Whether its sales tax, income tax, estate tax or property tax, the thought of mere taxation can infuriate most of the local citizenry, nobility or peasant alike. If not for taxes, after all, we would likely be speaking with British accents, and swearing fealty to the Queen.

A Taxing Situation

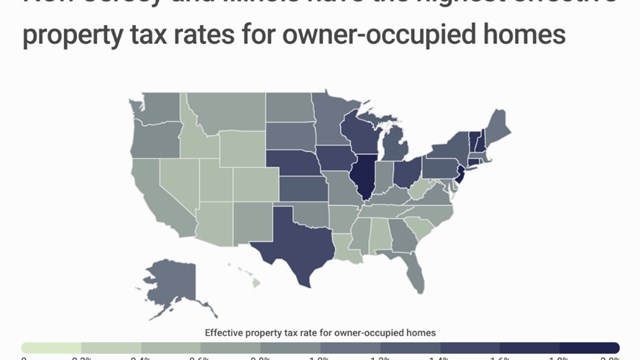

The issue of property taxes is a long-standing debate in the Garden State, where residents consistently have one of the highest tax burdens in the nation. New Jersey has been at or near the top of the list when it comes to how much individual residents pay in local and state taxes each year and according to the Tax Foundation’s recent survey, they currently rank third behind New York State and Connecticut.

New Jersey residents pay a lot of taxes, that’s a given. But when you take residential property taxes as a whole, New Jerseyans take the prize paying a whopping $8,354 in average taxes: the highest tax burden in the nation, according to some studies.

According to the Asbury Park Press study, property taxes rose approximately 8 percent in Asbury Park and Eatontown; 7 percent in Lakewood; 6 percent in Toms River; 4 percent in Freehold Township and Marlboro; and 3 percent in Long Branch, Middletown and Stafford. Other notable increases included 12.5 percent in Seaside Heights; 11 percent in Mantoloking; and 8.5 percent in Deal. The state Department of Community Affairs (DCA) came out with its own study in February and its results mirrored the newspaper’s.

The state data found that property taxes statewide jumped again in 2015—another 2.4 percent to an average payment of $8,353. That’s despite the state law restrictions imposed by Gov. Chris Christie five years ago limiting any year-over-year increases in the tax rate to just 2 percent.

Money, Money

For starters, out of New Jersey’s 566 municipalities, there are ten boroughs or townships that are literally breaking the bank in average taxes paid: Tavistock Borough (Camden County): $30,722; Millburn Township (Essex County): $22,734; Loch Arbour Village (Monmouth County): $21,662; Alpine Borough (Bergen County): $20,887; Mountain Lakes Borough (Morris County): $19,336; Tenafly Borough (Bergen County): $19,253; Rumson Borough (Monmouth County): $18,959; Essex Fells Township (Essex County): $18,718; Glen Ridge Borough (Essex County): $18,569; and Mendham Township (Morris County): $18,434.

On the flip side, the lowest average property taxes by municipality are: Downe Township (Cumberland County): $3,069; Bridgeton City (Cumberland County): $2,994; Dennis Township (Cape May County): $2,792; Commercial Township (Cumberland County): $2,443; Audubon Park Borough (Camden County): $2,192; Teterboro Borough (Bergen County): $1,960; Lower Alloways Creek Township (Salem County): $1,863; Walpack Township (Sussex County): $1,822; Woodbine Borough (Cape May County): $1,690; and Camden City (Camden County): $1,533

According to NJ.com, in 2015, nine counties, mostly along the shore or in the southern part of the state, rang up below $7,000 per home. Cumberland County, near Delaware, has the distinction of reporting the lowest average tax bill in the state, at $3,921, according to the DCA’s recent data released.

Stand and Deliver

Since his election in 2010, Christie has tried to stem the tide of rising taxes. In his 2017 Fiscal Year budget, he continues a property tax reform agenda to rein in government spending, cap interest arbitration, pension and health benefits awards, consolidate government benefits packages, and more. Annual property tax increases have averaged around 1.97 percent from the time he took office.

“This is the seventh time I have presented a budget to this chamber, and I’m proud to say this for a seventh time. This budget is balanced. And once again it is balanced through fiscal responsibility, and not on the backs of our citizens—for the seventh straight year, this budget imposes no new taxes on the people of New Jersey,” said Christie in his February budget address. The fiscal year 2017 budget calls for $34.8 billion in state appropriations, a 2.2% increase over the fiscal year 2016 budget.

While high property taxes, according to the website Wallet Hub, remain a major complaint among homeowners, municipal officials say they have to struggle to keep spending within the cap. Organizations such as the state League of Municipalities said other than staying within the cap there is little that legislators can feasibly do to control costs.

"It is a continual challenge to keep tax increases contained," Mike Cerra, assistant executive director of the New Jersey State League of Municipalities, told NJ Spotlight, a political website. "There are things we can't control. When it snows, we have to plow the roads, and we have had two bad winters in a row."

According to the state League of Municipalities, property tax accounts for around 45 percent of New Jersey’s state and local tax revenue, compared to a national average of just over 30 percent. New Jersey property taxes equal roughly 5.6 percent of personal income, compared with the national average of 3.6 percent. What does that revenue cover? In New Jersey, more than two-thirds of it is used to cover the cost of public education and that, for many, is where the problem lies.

Where the Money Goes

According to the state League of Municipalities, New Jersey’s tax system is determined by six basic factors: 1) the market value of the property that you own; 2) the cost of municipal and county programs and services; 3) the costs of your local public schools; 4 the availability of other revenues to cover those costs; 5) the extent of the presence of tax exempt properties in your municipality and; 6) by the total value of all the taxable properties in your municipality.

The Tax Foundation reports that New Jersey's individual income tax system consists of six brackets with a top rate of 8.97%. The top rate ranks 5th highest among states levying an individual income tax. New Jersey's state and local tax collections per person were $1,359 in 2013, which ranked 8th highest nationally. Forty-three states levy individual income taxes. Forty-one tax wage and salary income, while two states—New Hampshire and Tennessee—exclusively tax dividend and interest income. Seven states levy no income tax at all.

Tax Reform Efforts Still Thrive

Over the years, many tax reform groups have tried and failed to gain traction in getting real reform enacted. The American Reform Party has tried looking at alternative sources of revenue collection to reduce the average New Jerseyan tax burden.

Jackson resident George Kneisser heads up the New Jersey Citizens for Property Tax Reform, a grass-roots citizen effort to bring about tax relief that formed late in 2015. The group seeks to get 1 million signatures to petition the state Legislature to act. The group’s hypothesis is that according to the state League of Municipalities study, property taxes could be reduced by 35 percent by shifting half of the property tax burden onto income or sales taxes with minimal impact on payment of those levies.

The group’s petition also calls for a two-year freeze on increases in other taxes, and an annual hard cap on future increases of 2 percent or the annual consumer price index, whichever is lower. The group’s goal is to reduce property taxes an additional 20 percent by pursuing cost-cutting measures such as consolidation and regionalization of services.

A deadline of December 31, 2016 has been imposed by the group, and if no action occurs by that time, they propose to let the citizenry of New Jersey vote on the measures through referendum by June 30, 2017.

A bigger drop in property taxes would signal a need for larger income tax support for schools. New Jersey would need to replace about $14 billion that schools get from property taxes. That's equal to the approximate $13 billion the state collected in income tax in fiscal year 2015.

The petition is going well, says Kneisser, who vowed to continue an active fight to achieve real tax reform.

“Let me tell you my thinking. I don’t know much about why previous groups failed, but they were much too passive, just asking for reform,” says Kneisser. “We are a little different because we are going to fight for reform.”

He said the group intends to play an active role in the process, both legislatively and in bringing the issue before the public eye. “First of all, we’re going to ask the Legislature to do it, and if they don’t do it, we’re going to look into a legal path, and then force them to do it legally. We’re going to also do it on a campaign level going to some legislator’s districts and try to get them to explain what’s happened to the property tax for the last 15 years.”

“We’re reaching out to the public on one hand. We’re collecting all those signatures on the petitions. Going to the legislators: Of course, first, you always ask nice in the beginning. That’s what we’re doing. We’re telling them, ‘listen, the situation is unsustainable in New Jersey. Property taxes are going through the roof, and they keep going higher because there is nothing to stop them.’ Every year they go up. You’ve got to do something about it, and if you’re not going to do anything, we’re going to campaign against you through the people. We’re not just Republicans or Democrats, we’re just people.”

What impact has the high taxes had? Kneisser believes residents are leaving the state because of it. “If the Legislature doesn’t act, we’ll keep hitting them on that. Honestly, eventually they’re going to have to do something about it. They really cannot leave the state the way it is. We are almost in a crisis mode. I don’t know if you know what happened in Monmouth County last year—some people saw an increase of 20, 30, even 40 percent in their property taxes. So how can people stay in their house anymore, unless they’re making tons of money? “

Kneisser says he saw his own property taxes rising as he was reaching retirement age, and was inspired by articles in the Asbury Park Press to take action. The newspaper, which started its own legislative petition, said in its report that according to IRS data, multiple businesses and tens of thousands of residents had left the Garden State from 2010-2013, resulting in billions in lost revenue.

Asked if he had a message for political leaders, Kneisser said an emphatical yes. “It’s about time. They’ve been talking about it for maybe, 20 to 25 years. They all know it’s a problem, and unfortunately by them not doing anything they are becoming the problem. They are the problem. If they don’t do anything, they look at the problem and ignore it, they are the problem, and our problem is going to get worse. And eventually we’re going to get to a crisis point, and a financial meltdown. You cannot keep paying these high taxes on your house. Your house does not generate money,” Kneisser says.

“Your house is a necessity like food and shelter. You can’t be living in your house and be afraid five years from now that property taxes will be so high that you’re going to have to leave your house. So my message to Gov. Christie and the legislators is they have to do something and do it now—because otherwise they are becoming the problem.” To learn more and join the petition, Kneisser says residents can go to njptr.org.

When it comes to the health of the condo market in New Jersey and the well-being of the associations that run those condos, property taxes—as onerous as they are—seemingly have little impact on the overall real estate picture. However, a continuation of a pattern of high real estate taxes and local and state taxes will not make New Jersey as attractive to new homebuyers as it could be.

Ultimately, everyone from homeowners to political advocates to the members of the state Assembly on up seems to agree that measures must be taken to reduce the property tax burden on the people of New Jersey. Whether that reduction is achieved through new income sources or through budgetary cuts or consolidation or a reallocation of funds is yet to be determined. It may take a combination of solutions to achieve the right balance and the right solution for New Jersey homeowners. Whatever the answer, one thing is certain—the only thing that seems to grow year by year is the tax bill.

Debra A. Estock is managing editor of The New Jersey Cooperator. Freelance writer Liz Lent contributed to this article.

Leave a Comment